The ‘Subtle Simplicity’ of William Nicholson

William Nicholson - The Lustre Bowl with Green Peas

I recently enjoyed a trip down to Chichester to see an exhibition of the work of William Nicholson. (Pallant House until 10 May)

Nicholson was incredibly versatile. A printmaker, illustrator and designer, he also painted portraits, landscapes and still lifes. He had a gift for elegant clarity and quiet understatement, for keen-eyed observation.

‘’Must learn to observe.’ This maxim is as perfect for a painter as for a scientist.’

William Nicholson, quoting the scientist Michael Farraday

Nicholson was born in Newark-on-Trent in 1872, the youngest son of an industrialist and Conservative MP. Having trained in art in London and Paris, he collaborated with his brother-in-law James Pryde, under the name Beggarstaffs. Together they designed posters for Kassama Corn Flour and Rowntree’s Elect Coffee; for theatre productions of Hamlet, Cinderella and Don Quixote.

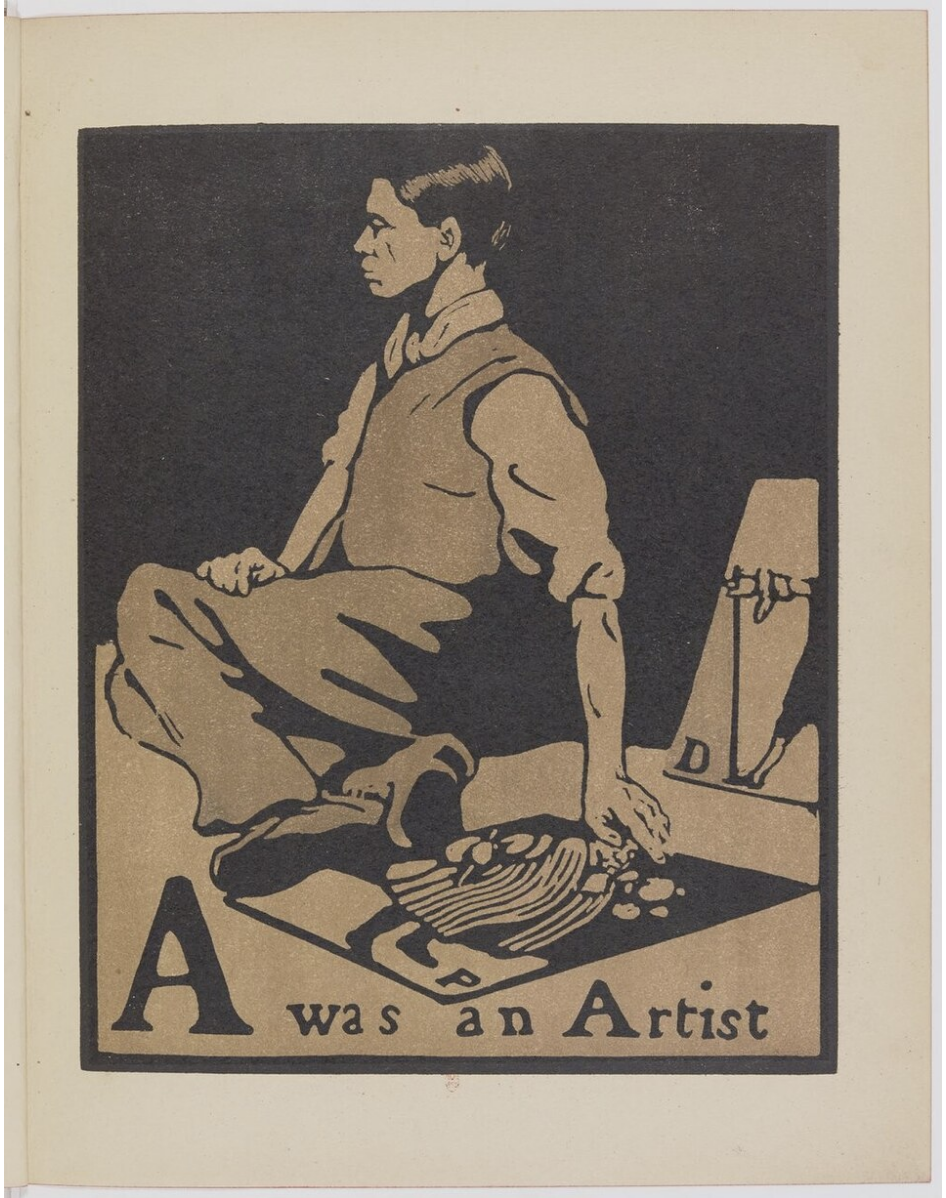

William Nicholson - A was an Artist

From the outset, Nicholson’s work was characterised by wit and sophistication; simplicity and restraint. He went on to produce illustrations for The Square Book of Animals, The Velveteen Rabbit, The Book of Blokes, and many more besides. He created woodcuts for a collection of London types - barmaid, guardsman, sandwich man, newsboy - and a pictorial alphabet - A is for Artist, B is for Beggar, C is for Countess…

And D is for Dandy. Nicholson was something of a dapper dresser. In ‘A Bloomsbury Family’, William Orpen painted him in starched collar and yellow waistcoat, wrapped in his favourite black and white polka-dot dressing gown, a black slipper dangling from one foot. His children, gathered round the table, look bored. His wife Mabel Pryde, in smart Edwardian attire, stands at the back and reaches for the door.

William Orpen - ‘A Bloomsbury Family’

Gradually Nicholson turned to portraiture as a reliable source of income. Essayist Max Beerbohm is rather solemn, his top hat and stick casting a shadow against a bare wall. Social reformers Sidney and Beatrice Webb warm themselves by the fire, a terrier at their feet. Actress Wish Wynne, wearing a maid’s outfit for a performance, turns her back. And blonde-bobbed artist Diana Low, set against a primrose curtain, looks confidently straight out at us.

It is thought that Nicholson used his son Tony as the model for his 1917 portrait of a First World War soldier in goatskin jerkin, peering over the lip of a trench. The following year, Tony died from wounds received in action, and Mabel fell victim to the Spanish flu.

‘It is difficult to rebuild in words what one records in paint.’

William Nicholson - Miss Wish Wynne, Actress, in the Character of Janet Cannot for the Play 'The Great Adventure''

Nicholson expanded his artistic repertoire further still. He painted the landscapes of Sussex and the Downs: rolling hills and luminous skies, verging on abstraction. He painted still lifes that explored the relationship between light and dark. Affectionate depictions of treasured objects, they dazzle and enchant.

Some flowers in a mug rest on top of a pile of books. A Lowestoft bowl stands beside some cut tulips and one melancholic fallen petal. There is a silver bowl on a white tablecloth, another accompanied by a fan and tassel; a lustre bowl with green peapods; a brass canister with a quill and some journals; a ruby glass with a necklace, a gold jug. A silver casket is carefully placed on a vibrant red leather box, a pair of white gloves to one side.

These are modest, understated images. In their stillness, they prompt the viewer to pause, to reflect in silent wonder. The metal objects shimmer in the light, catching reflections. If you stand up close, you can see that Nicholson has achieved a luminous effect with just a flick of a brush loaded with white paint.

William Nicholson - Gold Jug

Though Nicholson’s art celebrated simplicity, he had a complex family life. He had a long-running affair with his housekeeper, and, after Mabel’s death, he married a family friend who had also been close to his son Ben. Somehow, they navigated the situation. His children went on to form a creative dynasty, with Ben becoming an artist, Nancy a designer, and Kit an architect.

Nicholson picked up the pots, jugs and other ceramics that featured in his still lifes in the Caledonian Road market, second hand shops and pubs. He also collected silver, and was a particular fan of the work of 18th century silversmith Hesther Bateman. He wrote to a friend:

‘Hesther Bateman… was a wonderful artist. I have four or five of her silver masterpieces. Subtle simplicity is her ‘note.’’

The phrase could equally be applied to Nicholson’s work.

Simplicity is hard to attain. It requires focus and sacrifice; moderation and restraint. It demands that we make deliberate choices, that we learn to say ‘no’. Ultimately, as Leonardo observed, ‘simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.’

'I don't believe in fretting and grieving,

Why mess around with strife?

I never was cut out to step and strut out,

Give me the simple life.

Some find it pleasant dining on pheasant,

Those things roll off of my knife.

Just serve me tomatoes and mashed potatoes,

Give me the simple life.

A cottage small is all I'm after,

Not one that's spacious and wide.

A house that rings with joy and laughter,

And the ones you love inside.

Some like the high road, I like the low road,

Free from the care and strife.

Sounds corny and seedy, but yes, indeed,

Give me the simple life.'

Etta Jones, 'Give Me the Simple Life’ (R Bloom, H Ruby)

No. 551