The Pointillist Dilemma: Can Painstaking Precision Express or Elicit Passion?

Henry van de Verde (1863-1957) - Avondschemer (Twilight) c.1889. Oil on Canvas

I recently visited an exhibition of Pointillist works. (‘Radical Harmony’ is at the National Gallery, London until 8 February, 2026.)

‘Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science.’

Georges Seurat

Pointillism is the painting technique whereby small, distinct dots of pure, complementary colours are applied in patterns to form an image. Developed by artists such as Georges Seurat and Paul Signac in the 1880s, it was based on colour theory and the study of optics. Viewed from a distance, the colours were believed to ‘blend in the eye’ to create vibrant, nuanced tones and an illusion of light.

Georges Seurat (1859 -1891) - Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp 1885. Oil on Canvas

The artists themselves balked at the term Pointillism. (Seurat and Signac preferred Divisionism.) However it was labelled, the approach particularly lent itself to landscapes. Blue and orange, red and green, yellow and white dots and dabs cohere to form waves lapping against sandy beaches, clouds melting into the horizon, dunes extending into the distance. In the soft morning light, boats are moored by the river, birds flutter over jagged rocks, a lighthouse looms on a far-away shore. At dusk a lone, hunched woman treads the village path, deep in thought.

These shimmering outdoor scenes, verging on abstraction, seem still and silent. They have an austere, dream-like, spiritual beauty.

This distinctive artistic movement was regarded as radical in its time. Camille Pissarro called it ‘a new phase in the logical march of Impressionism.’

Maximilien Luce (1858-1941) - Morning, Interior (1890). Oil on Canvas

However, some in the art establishment were sceptical of Pointillism’s scientific basis and painstaking process, describing it as ‘the death of painting.’ One critic complained of 'landscapes that look as though they have been made by artillery and confetti.'

Some of the Pointillists shared an interest in anarcho-communism – a political movement which championed the rights of working people. In an increasingly industrialised age, they painted the struggles of the lower classes, or an idealised vision of social harmony.

Sunlight streams into a modest room, as an artisan puts on his boots to start his day. Teams of men are silhouetted by the blazing blast furnace. On the evening before a strike, a man holds his hands to his head in despair.

‘Justice in sociology, harmony in art: same thing.’

Paul Signac

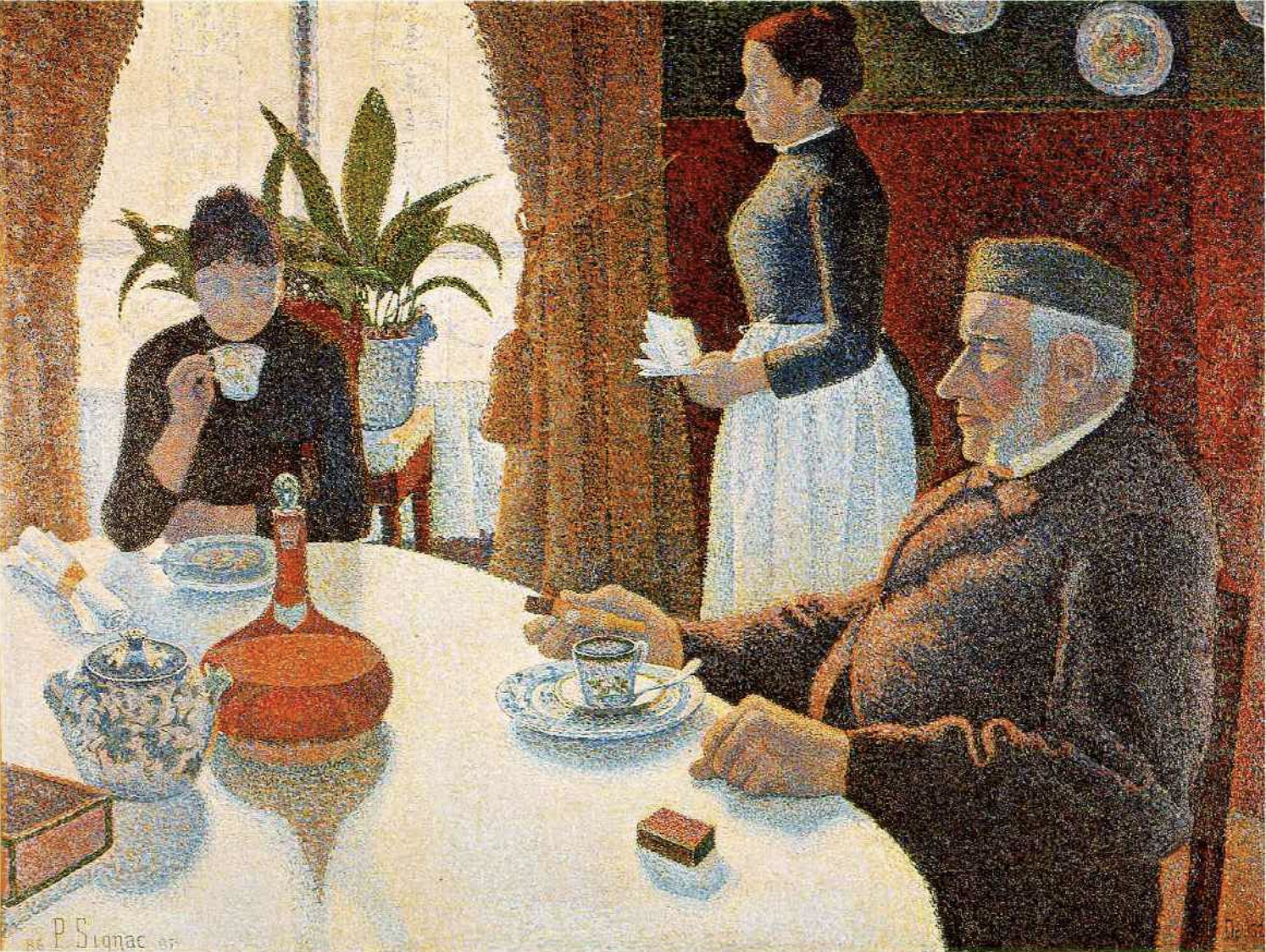

Paul Signac (1863-1935) - La Salle à Manger (The Dinning Room) c1886. Oil on canvas.

The Pointillists also turned their attention to portraits and interior scenes.

In the summer heat, five women in white linen relax in an orchard. Another sits in the garden, absorbed in her book. A lady shows off her bright orange dress. A husband stokes the fire, while his wife turns away to look out of the window. It’s breakfast-time in a middle-class home: as the maid brings the morning newspaper, the mistress sips her coffee and an elderly man puffs at his cigar, in solemn silence.

The figures can come across as somewhat isolated, lost in their own worlds. There is an intimation of boredom and domestic estrangement.

This sense of the uncanny, of alienation, may be by design. But one also suspects that these images display the limitations of the style. In adhering to academic rigour, in painstakingly applying the technique, there seems a stiffness, a loss of passion and emotion. The pictures come across as rather bloodless.

This poses a challenge for anyone working in a creative discipline. We may on occasion fall slaves to method and ideology. Sometimes executional exactitude and obsession with detail can constrain us. We must always leave room for true expression and raw emotion.

Pointillism captured the imagination of the artistic avant-garde for a number of years. Pissarro and Vincent Van Gogh experimented with their own versions of the technique, the latter employing strokes rather than dots. But the approach was restrictive, a cul-de-sac. In his later work, Signac became increasingly spontaneous, and other Pointillists gave up its rigours entirely. Seurat, who occasionally criticised his fellow artists for their lack of intellectual purity, continued to adhere to the theory. However, in 1891 he died, aged just 31. As the decade progressed, Pointillism’s influence waned.

'If you really love him,

And there′s nothing I can do,

Don't try to spare my feelings,

Just tell me that we′re through.

And make it easy on yourself,

Make it easy on yourself.

'Cause breaking up is so very hard to do.

And if the way I hold you

Can't compare to his caress.

No words of consolation

Will make me miss you less.

My darling, if this is goodbye,

I just know I′m gonna cry.

So run to him,

Before you start crying too.

And make it easy on yourself,

Make it easy on yourself.

‘Cause breaking up is so very hard to do.’

Jerry Butler, 'Make It Easy on Yourself’ (B Bacharach, H David)

No. 547