‘An Intenser Expression’: David Bomberg on Building Life and Art Anew

David Bomberg 1890–1957 Vision of Ezekiel 1912

'We must build our new art life of today upon the ruins of the dead art life of yesterday.’

David Bomberg

I recently visited a small exhibition of the early work of British artist David Bomberg. (The National Gallery until 1 March.)

Bomberg was born in Birmingham in 1890, the seventh of eleven children. His parents were Polish Jewish immigrants who subsequently settled in Whitechapel in London’s East End. He grew up in poverty, but single-mindedly pursued an artistic career. After a chance encounter at the V&A with the established painter John Singer Sargent, he gained a place at the Slade School.

‘I hate the Fat Man of the Renaissance.’

Whereas the British art establishment of the day steadfastly resisted the innovations that were taking place on continental Europe, Bomberg was one of a number of young painters who were emboldened by the likes of Picasso and Matisse. He gradually developed a radical style that combined the abstraction of cubism with the dynamism of futurism.

When he was 22 Bomberg’s mother died of pneumonia. She was just 48. He channelled his grief into 'Vision of Ezekiel,' a work that considered the biblical story in which a prophet is taken to the Valley of Dried Bones and witnesses their resurrection.

'And he said unto me, Son of man, can these bones live? And I answered, O Lord God, thou knowest.'

Ezekiel, Chapter 37

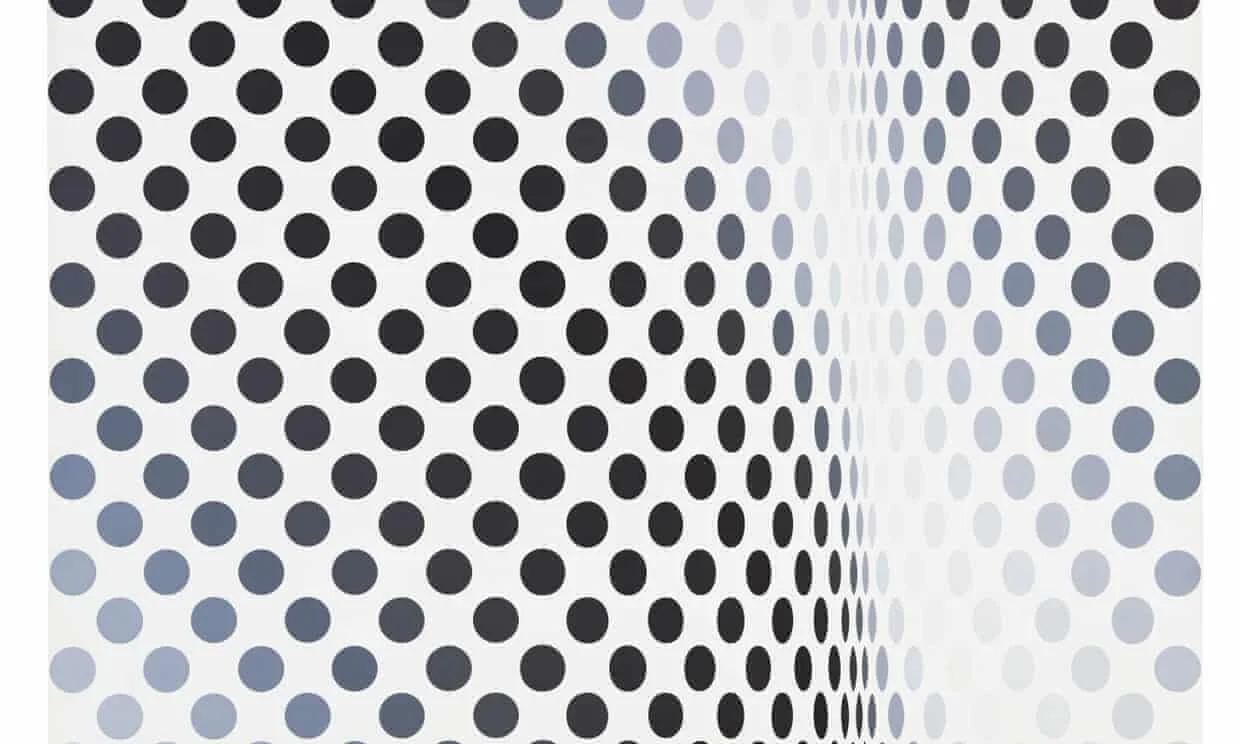

The geometric figures in ‘Vision of Ezekiel’ dance with pure joy, hug one another, and raise their hands ecstatically to the heavens. They are in awe at what has happened to them, animated with a renewed lust for life. It is a heartfelt work.

Detail from David Bomberg In the Hold, about 1913-14 © Tate

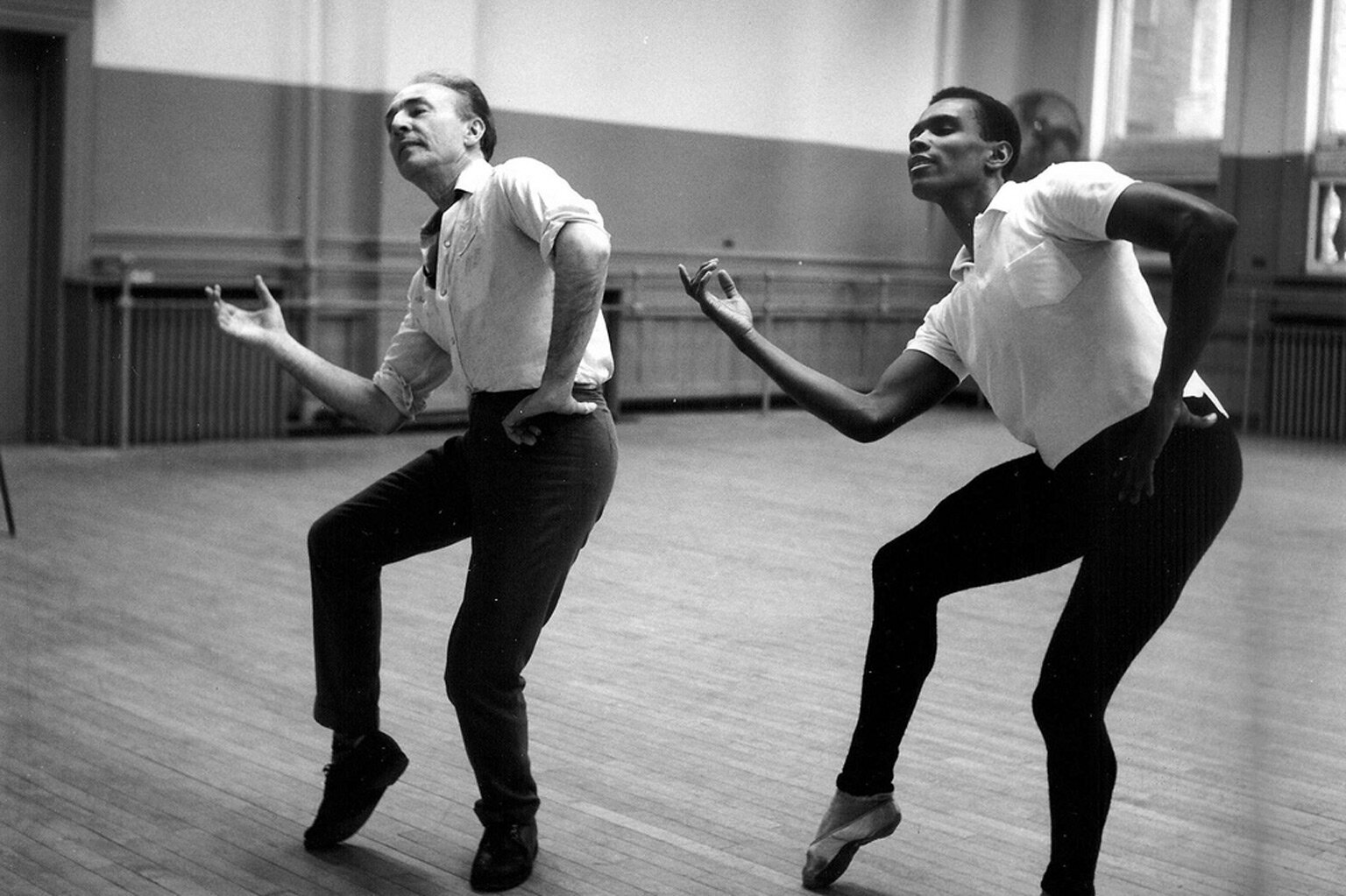

Bomberg’s paintings around this time responded to his family’s experiences and to the world around him. He was inspired by the muscular activity at the Judeans gymnasium where his brother trained as a boxer; by the dramas played out at Saint Katharine’s Wharf where ships brought in human cargoes of immigrants; by the raw physicality that he witnessed at Schevzik’s Vapour Baths in Brick Lane where locals went in search of ‘purification.’

Bomberg created sharp, angular abstractions, teeming with energy, vibrant with colour. There were jagged elbows, taught necks, arms aloft and legs akimbo. Stretching and straining, squatting and stooping. Wrestling, embracing, gripping and grasping. Holding on for dear life. His paintings had an urgency about them, an electric charge, a vital sense of struggle.

Bomberg’s progressive thoughts and rebellious attitude got him expelled from the Slade. But he forged ahead, and within a year, in 1914, he was given a show at the Chenil Gallery, Chelsea. In the catalogue he wrote:

'In some of the work… I completely abandon Naturalism and Tradition. I am searching for an Intenser expression. In other work… where I use Naturalistic Form, I have stripped it of all irrelevant matter.’

Perhaps there is a lesson for us all here. So often in work and life we compromise, concede and dilute. We waste time and energy. We allow ourselves to be caught up in the trivial and superficial, the bland and banal.

If we truly want to ‘build our new life of today’ the answer may reside in ‘stripping away irrelevant matter’; in finding more concise, more concentrated articulation of our feelings; in seeking out heightened experiences. We need to find ‘an intenser expression.’

David Bomberg, The Mud Bath, 1914. © Tate

With the onset of the First World War Bomberg enlisted and served in the trenches on the Western Front. Like many of his comrades he turned to poetry as an outlet. Distraught at the death of his brother and many of his friends, in 1917 he shot himself in the foot. He was fortunate to escape a firing squad.

After the conflict Bomberg’s experiences prompted a change in artistic direction. He increasingly painted portraits and landscapes, embracing a more figurative style. The radicalism of cubism and the optimism of the machine age just didn’t feel relevant any more.

‘Hemmed in. The bolted ceiling of the night rests

on our heads, like vaulted roofs of iron huts the troops

use out in France, - unlit. Grope – stretch out your

hand and feel its corrugated sides, rusted,

Dimly seen, six wiring-stakes driven in the ground,

askew, some yards apart; - demons dragging, strangling -

wire. Earth and sky, each in each enfolded -

hypnotised; - sucked in the murky snare, stricken dumb.’

David Bomberg, ‘Winter Night’

No. 266