Seeing Yourself from Unexpected Angles: Truth Telling by Lucian Freud

Reflection with Two Children (Self-Portrait) - Lucian Freud

‘With self-portraits ‘likeness’ becomes a different thing, because in ordinary portraits you try to paint the person in front of you, whereas in self-portraits you’ve got to paint yourself as another person.’

Lucian Freud

I recently attended an excellent exhibition of Lucian Freud’s self-portraits (at the Royal Academy, London, until 26 January 2020).

Freud is renowned as a portraitist of quiet intensity. He engaged in what he called ‘biological truth telling,’ endeavouring to capture the physical reality of his sitters: his wives and mistresses, daughters and dogs, friends and acquaintances.

‘I work from the people that interest me and that I care about and think about in rooms that I live in and know.’

Typically Freud painted in his studio standing at his easel, applying thick layers of paint to the canvas with his large hog’s-hair brushes. He had his subjects sprawl naked on the floor, on a sofa or bed, at unusual or uncomfortable angles. His process involved long sittings and could take weeks or months. One woman needed osteopathy after her portrait. His conversation was light and witty, but his gaze was direct, frank and sometimes unsettling.

Freud was particularly adept at capturing the texture and colour of flesh, employing Cremnitz White to suggest the skin’s luminous qualities.

‘I want paint to work as flesh.’

Startled Man: Self Portrait, 1948. Photograph: © The Lucian Freud

Freud believed that, even when he painted other people, he was always painting himself – his perspective, his point of view, his particular relationship with the sitter.

‘My work is purely autobiographical. It’s about myself and my surroundings.’

And so when Freud painted his son Freddy we see the artist’s own reflection in the window. When he painted ‘Flora with Blue Toenails’ his shadow looms ominously over her in the foreground. And look, there are Freud’s feet at the foot of that sofa. There are a couple of his self-portraits leaning against a wall. He is ever present.

'I thought, after putting so many other people through it, I ought to subject myself to the same treatment.'

Freud painted or drew his own image throughout his life. He holds up a white feather to us, a gift from his first girlfriend. He regards us through a houseplant, from the side of his wife’s bed. He looks startled and surprised - open mouthed and wide eyed, as if he has seen himself for the very first time. His lips are fleshy, his nose slightly twisted, his stare piercing. He appears sceptical, challenging. His face is covered in shadows that suggest the contours of his soul: a landscape of doubt, misgivings and resentment.

Bur despite his famous grandfather, Freud resisted psychological interpretations of his work. He was seeking physical not spiritual truth. He often drew his own image in his notebooks. Here we see his roughly sketched face surrounded by cryptic words: Prudent Miss, High Authority, Time To Reflect. We think for a moment that this may signify something rather important. And then realise he’s calculating his next bet on the horses.

'Self-Portrait with a Black Eye' - Lucian Freud

On one occasion Freud came away from an argument with a taxi driver with a black eye. He rushed back to the studio to capture his disfigured face, the dark swollen mess that his left eye had become.

‘I don’t accept the information that I get when I look at myself and that’s where the trouble starts.’

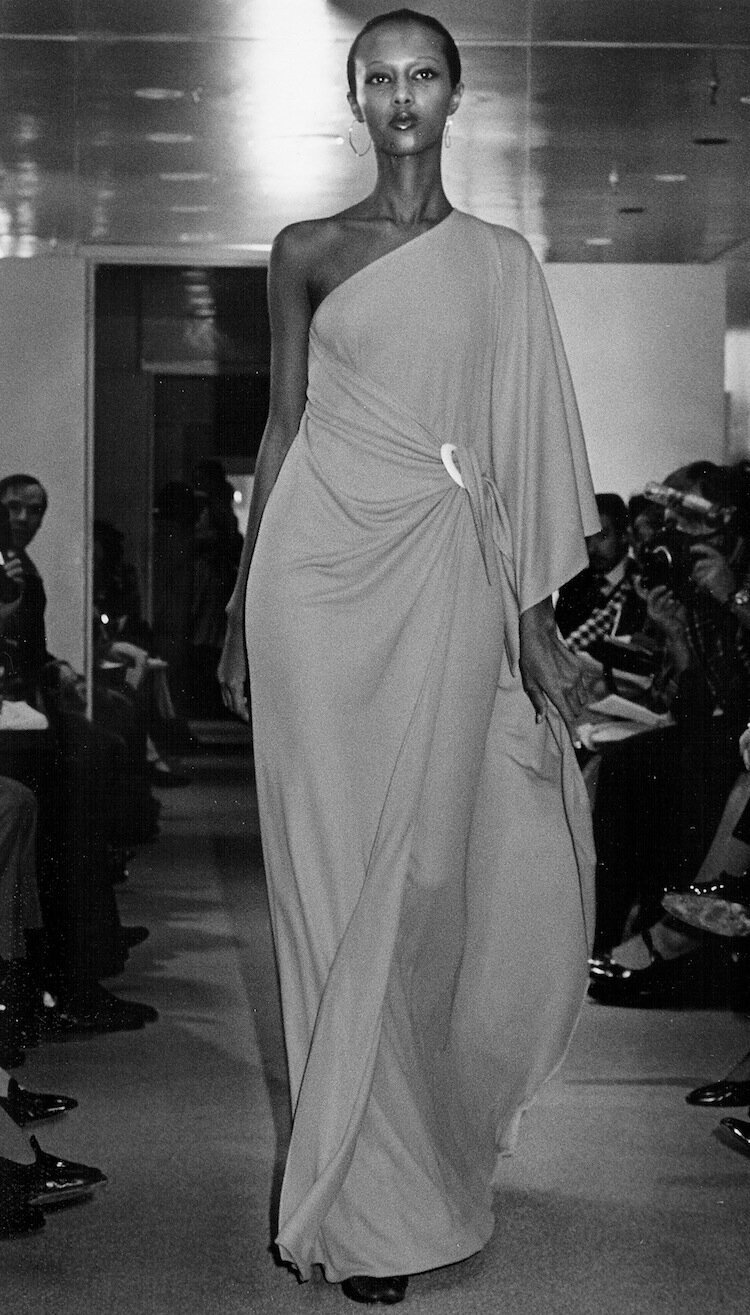

Freud painted himself with the aid of mirrors rather than photographs. He preferred natural light. Although he avoided having mirrors about the house, he set them up at various places around his studio, so that he could catch himself from unexpected angles. For ‘Reflection with Two Children’ he placed a mirror on the floor. He towers over us, his body foreshortened, sinister and threatening. Two of his children stand outside the composition. Are we seeing a child’s eye view of their father?

Of course, most of us nowadays are given to self-reflection in some form or another. We like to consider and compare our appearance, our character, our achievements. But for the most part we tend to look in the mirror square-on. We see a consistent picture of ourselves, from just one perspective. It is merely selfie-awareness.

Freud suggests that we should be sceptical of this image; that we should try to capture ourselves unawares; to see ourselves as others see us. If we want a proper reflection of our true self, why not ask our friends and colleagues, our partners and families? How do you see me? What do you make of me? What are my strengths? Where am I going wrong? We should seek to see ourselves from unexpected angles.

'I don’t want to retire. I want to paint myself to death.’

When he was 70 Freud painted himself nude for the first time. With unflinching frankness he conveyed the frailty of his ageing body, posing with unlaced boots, brandishing his easel and palette knife, proud of the tools of his trade. He kept reworking the portrait over several months, never quite satisfied.

‘I couldn’t scrap it, because I would be doing away with myself.’

'One day you're going to have to face

A deep dark truthful mirror.

And it's going to tell you things that I still love you too much to say.’

Elvis Costello, ‘Deep Dark Truthful Mirror'

No 256