Love and Ambition: You Can Only Excel at Work If You Love What You Do

I recently watched a couple of excellent documentaries about two troubled musical geniuses, Janis Joplin and Michael Jackson. Focusing less on the demons that haunted these artists in their personal lives, the films shed light on the character traits that drove them to achieve so much creatively.

I was struck by the fact that both Joplin and Jackson were decidedly ambitious, but that for them ambition was not about material or reputational success; it was about love.

Janis: Little Girl Blue

Janis Lyn Joplin, born in 1943, grew up in a conservative household in Port Arthur, Texas. From the start she was independent minded and rebellious. At an early age she fell in love with the rich blues sound of the likes of Bessie Smith and Big Mama Thornton. It was a love that sustained her through a tough time at school, where she was bullied for her liberal views, her unconventional looks and her refusal to conform to notions of Southern femininity. Often such lonely souls find solace at college. But at the University of Texas Joplin was similarly an outsider. A fraternity house voted her ‘the ugliest man on campus.’ It’s a wretched, heart-rending moment in the film.

‘And each time I tell myself that I think I’ve had enough.

But I’m gonna show you, baby, that a woman can be tough.

I want you to come on, come on, come on, come on and take it.

Take it!

Take another little piece of my heart now, baby.’

Big Brother and the Holding Company, Piece of My Heart (Bert Berns/ Jerry Ragovoy)

Joplin escaped to the burgeoning hippy scene of San Francisco and Haight-Ashbury. There, for the first time, she felt accepted and at home, and she found the confidence and kindred spirits to perform the music she cared for. She had a raw, powerful blues voice that was at once uninhibited and vulnerable.

Sadly the psychedelic community that saved Joplin, also encouraged the addictions that killed her. In 1970, aged just 27, she died of a heroin overdose. She left behind essential recordings like ‘Cry Baby’, ‘Ball ‘n’ Chain’, 'Little Girl Blue' and ‘Piece of My Heart’; timeless anthems to struggle and pride, devotion and loss.

‘I know you’re unhappy. Baby, I know just how you feel.’

Janis Joplin, Little Girl Blue (Richard Rodgers/ Lorenz Hart)

Janis Joplin was certainly rebellious and uncompromising. But in her letters home she revealed a thoughtful, tender side to her personality.

‘I’ve been looking round and I’ve noticed something. After you’ve reached a certain level of talent, and quite a few have that talent, the deciding factor is ambition, or, as I see it, how much you really need, need to be loved and need to be proud of yourself. And I guess that’s what ambition is. It’s not all a depraved quest for position or money. Maybe it’s for love.’

Janis Joplin, in a letter to her mother, Janis: Little Girl Blue

Joplin’s insight poses questions for everyone working in the field of commercial creativity. How many of us are driven to perform by the desire for status or material success? How many can genuinely claim to do it for love? And can that love sustain us through the hard times and human frailties that life and career have in store for us?

Michael Jackson’s Journey from Motown to Off the Wall

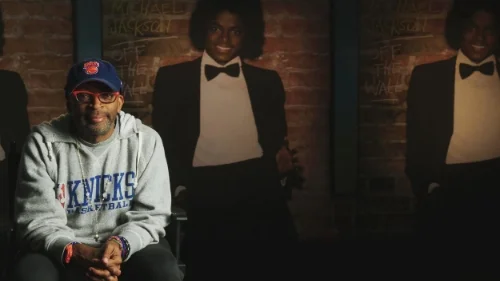

Michael Jackson in In New York City in 1977 Tom Keller - Getty Images

I grew up in Essex, the home of the British soul boy. We sported floppy wedge haircuts, white socks and cut down loafers; we wore pastel shaded shirts and sleeveless sweaters. We loved to dance. For us Michael Jackson wasn’t about ‘Thriller’ and ‘Bad’ and the ‘King of Pop’. He wasn’t about ‘Dirty Diana’ or ‘Earth Song’. This crossover music was anathema to us.

No. Michael Jackson was the child genius at the heart of the Jackson 5, the exuberant force of nature who belted out ‘ABC’, ‘I Want You Back’ and ‘The Love You Save’; he was the adolescent yearning of ‘Ben’; the dance floor dynamism of The Jacksons and ‘Blame It on the Boogie’. He was the irrepressible insistence of ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’; the sublime sophistication of ‘Rock With You’. Above all, in 1979 he was the author of ‘Off the Wall’, the definitive document of aspiration and optimism, hedonism and longing; of what it was to be young.

Spike Lee’s excellent documentary, ‘Michael Jackson’s Journey from Motown to Off the Wall’, puts the focus back on the best parts of Jackson’s life; on the soul genius, the dance divinity; on Jackson before the Fall.

In the documentary we see a letter Jackson wrote when he was twenty, setting out his ambition to put his past triumphs behind him and to write a new chapter in entertainment history.

‘MJ will be my new name. No more Michael Jackson. I want a whole new character, a whole new look. I should be a totally different person. People should never think of me as the kid who sang ‘ABC,’ ‘I Want You Back.’ I should be a new incredible actor, singer, dancer, that will shock the world. I will do no interviews. I will be magic. I will be a perfectionist, a researcher, a trainer, a master. I will be better than every great actor roped in one. I must have the most incredible training system. To dig and dig and dig until I find. I will study and look back at the whole world of entertainment and perfect it. Take it steps further from where the greatest left off.’

Michael Jackson, 16 November 1979

There are a number of compelling things about Jackson’s ambition. Firstly, one is struck by its breadth: his aspiration is unconstrained by traditional career categories. Also he believes he can only progress if he frees himself from his own past successes. Ambition must look forward, not back. And yet, at the same time, he commits to being a diligent student of the past successes of others. ‘We often invent the future with fragments from the past.’ (Erwin Panofsky)

We are drawn to the conclusions that Janis Joplin herself made: that creative success is founded on talent, hard work and ambition; and that ultimately you have to love what you do.

Verdine White, the bassist in the phenomenal Earth, Wind and Fire, sums up Jackson’s success thus:

‘You got to put the work in, man. You got to put the time in. And really, man, it’s love that you’re putting in. You know, because people that do this kind of thing, man, we love what we do.’

Verdine White, Earth, Wind and Fire

Love and Ambition at Work

I suppose this all leaves us asking questions about our own ambition.

Do we have the determination to put the hours in? Is our ambition constrained by conventional job definitions and expectations? Do we have the vision and appetite to put our previous successes behind us? Do we at the same time have the dedication to study the successes of others, the history of our craft?

And on a fundamental level, do we love what we do?

I find I personally have a mixed response to these questions. I certainly put the hours in. But I suspect that sometimes I was too nostalgic about past victories; too fond of rose tinted recollection. Yes, I wanted to know more about my craft. But then the pressures of the immediate often prompted me to set aside that key text; to save it for a day that never came.

Did I love my job? Well certainly not all of it. But most of it, yes. I loved learning the art of persuasion and the idiosyncrasies of popular culture; the discipline of distillation and the freedom of the lateral leap; I loved the theatre, the thrill of the chase; tackling the commercial conundrum and being part of a diverse company culture; I loved the optimism of my younger colleagues and the scepticism of my elders. I guess I may not always have loved work, but I did love the work.

And perhaps this is the most important lesson. It would be hard to expect anyone to love everything about their job. So we must find the aspects of work that we do genuinely love and focus our energies on these.

The conclusion is perhaps inevitable. We can only excel at work if we love what we do. And the easiest way to love what we do is to do what we love.

‘So tonight gotta leave that nine-to-five upon the shelf,

And just enjoy yourself.

C’mon and groove, and let the madness in the music get to you.

Life ain’t so bad at all,

If you live it off the wall.’

Michael Jackson, Off the Wall (Rod Temperton)

No. 83