The Bias Cut: Halston and the Perils of Brand Extension

Photography © Dogwoof

‘I believe in our country, and I like America, and I want Americans to look good. And I’m an American designer and I want the opportunity to do it.’

Legendary US designer Halston, on signing a 5 year licensing deal with JC Penney

I recently saw a fascinating documentary about the American fashion legend, Halston (‘Halston' a film by Frédéric Tcheng). It’s the story of a designer who was instinctively in tune with his times, who rewrote the rule book, but who ultimately fell victim of his own success. It’s a story that teaches us a good deal about the perils of brand extension.

Roy Halston Frowick was born in Des Moines, Iowa in 1932. Having developed an early interest in sewing, he moved to Chicago, found work as a window dresser and enrolled in a night course at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1953 he opened his own milliners business, which was quickly successful. Soon he was creating hats for the likes of Kim Novak, Gloria Swanson, Deborah Kerr and Hedda Hopper.

In 1957 Halston moved to New York where he was appointed head milliner for high-end department store Bergdorf Goodman. He gained wider celebrity by putting Jackie Kennedy in a pillbox hat for JFK’s 1961 inauguration. In 1968 he opened his first womenswear boutique on Madison Avenue.

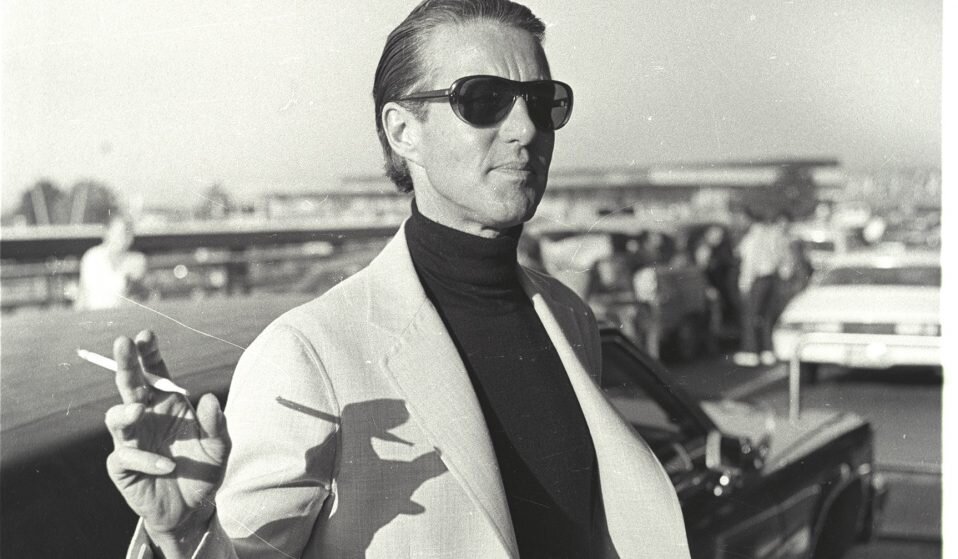

‘I’m the all-time optimist and I like it right now.’

Halston in New York in 1980. Credit: SAUER Jean-Claude/Paris Match Archive/Paris Match via Getty Images

Halston’s style was right for the emancipated ‘70s. He was a minimalist and he began by stripping away what he saw as the unnecessary elements of female fashion:

'All of the extra details that didn't work - bows that didn't tie, buttons that didn't button, zippers that didn't zip, wrap dresses that didn't wrap. I've always hated things that don't work.'

This resulted in clothes that were unstructured and unrestricted, relaxed and carefree - clothes more suited to times of liberation and social change.

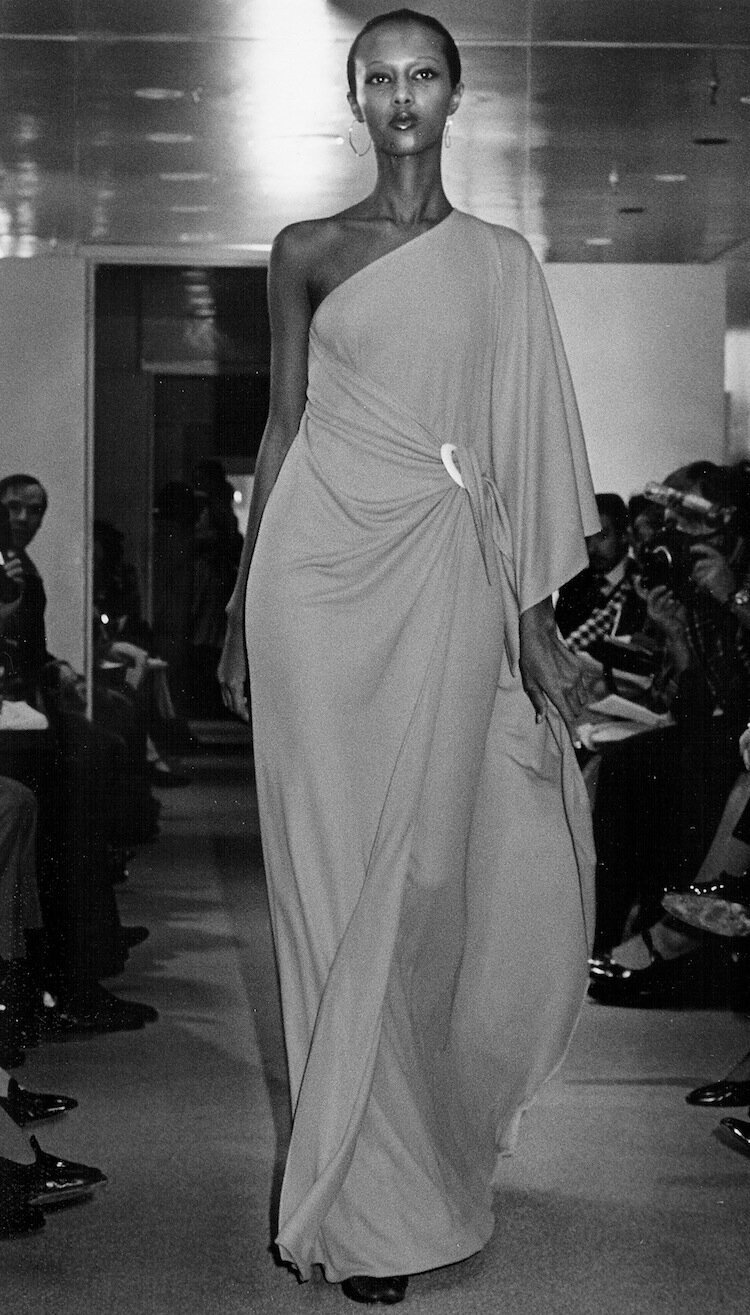

Iman walks the runway in a Halston jersey dress in spring 1976, Pulse Magazine

‘He took away the cage, and he made things as though you didn’t really need the structure as much as you needed the woman.’

Pat Cleveland, Model, ‘Halston’

Halston favoured the bias cut: cutting cloth on the diagonal (at 45 degrees) rather than following the straight line of the weave. The technique caused the fabric to fall naturally over the body, creating sensuous curves and soft drapes. His clothes had a fluid functionality, elegance and ease. They were simple yet sophisticated, glamorous yet comfortable.

‘Fabric to Halston was like clay to a sculptor.’

Chris Royer, Model

Halston designed for the international jet-set, for professional women and the discotheque. He eroded the divide between womenswear and menswear, between night and day. He worked with soft silks, sequins and satin, with chiffon and ultra-suede. He produced hot pants and halter-tops; suits and shirtdresses; cutaways, kaftans and capes - all finished off with a flamboyant big belt.

‘You were free inside your clothes.’

Karen Bjornson, Model

Halston was a natural publicist. Subscribing to the view that ‘You’re only as good as who you dress,’ his boutique drew celebrity clients like Anjelica Huston, Lauren Bacall, Elizabeth Taylor and Liza Minnelli.

‘His clothes danced with you.’

Liza Minnelli

Halston, bottom left, and models in his designs. Photographed by Duane Michals,Vogue, December 1, 1972

Halston brought a sense of theatre to everything he did. He turned up at events accompanied by an array of his favourite models, the Halstonettes. He styled the 1972 Coty Awards as a talent show, climaxing with ex-Warhol actor Pat Ast emerging dramatically from a cake. In 1977 he threw a 30th birthday party for Bianca Jagger at Studio 54. Sitting atop a white horse, she was led around the dance floor by a naked giant covered in gold glitter.

The Urge to Expand

Halston was driven by an ambition to move forward, to grow, to reach more people.

'I don’t quite know where I got my ambition but I have it. I go into things with an optimistic point of view and I look at it straight and try to make it the biggest and best success I can. But the thing that holds my interest always is MORE - what’s next, what’s going to be the next exciting thing?'

In 1973, in order to fund expansion, Halston sold his company to Norton Simon Inc, a conglomerate whose properties included Max Factor and Canada Dry. The deal afforded him huge financial backing and he remained principal designer with complete creative control.

Norton Simon felt they were buying instant access to fashion credibility.

‘We wanted a top perfume and he was the hottest thing around. I just wanted to buy the whole thing. Just to have him on board for his general knowledge of panache.’

David Mahony, President, Norton Simon Inc

The auspices seemed good, and Halston dealt confidently with anyone querying the wisdom of the sale.

‘It’s rather like growing a tree. Everyone thinks that you’re an overnight success. I’ve worked very hard for 20 years, and you know it’s just a further extension of it. It’s another branch. And they all help each other in a curious way.’

The Honeymoon

In the early years the new corporate partnership went incredibly well.

At the legendary Battle of Versailles Fashion Show of 1973 Halston’s presentation, fronted by Liza Minelli and making extensive use of black models, put America at the forefront of the global fashion industry.

‘All that energy and that joy and that wonder and that curiosity. Well, that is America!’

Liza Minnelli

In 1975 Max Factor released Halston's first branded fragrance for women. With its distinctive teardrop bottle design by Elsa Peretti it was an immediate success.

Halston expanded his line to include menswear and cosmetics, homeware and handbags, shoes and sunglasses, luggage and lingerie. He designed the uniforms for the 1976 US Olympic team, for Braniff Airways and Avis, for the Martha Graham Dance Company and the US Girl Scouts. He created the gold outfits for Sly Stone’s 1974 wedding at Madison Square Garden.

Indeed everything Halston touched turned to gold. In 1978 he moved his headquarters to the 21st floor of Olympic Tower on Fifth Avenue. The offices were adorned in white orchids and every wall was covered floor-to-ceiling in mirrored glass.

"Halstonettes" Pat Cleveland, Chris Royer, Alva Chinn and Karen Bjornson in 1980 - Photo, Dustin Pittman

The Cultural Tension

However, there were inevitably tensions between the corporate owners and the high-end fashion house. Prior to the launch of Halston’s fragrance, Max Factor executives complained about a bottle that couldn’t be filled from the top and branding that was limited to a ribbon round the pack.

In 1982 Halston signed a 5 year licensing deal with JC Penney, the archetypal mainstream department store. Halston was typically bullish about the move.

‘It’s really the third stage of my career. The first being in the millinery business, and then in fancy clothes and dressing all the stars… and now a larger public - dressing America really.’

The media talked about Halston moving ‘from class to mass.’ The President of Bergdorf Goodman deemed this a brand stretch too far and immediately delisted all Halston products from their stores.

Penney merchandisers began to complain that Halston’s working methods didn’t mesh well with their own.

‘He’s got to understand that we’ve got to commit like at least 8 months in advance. We need to get the approvals and the go-aheads and the concepts. But he’s so involved with everything that…the label took him months.’

JC Penney Merchandiser

The Troubled Genius

Halston was committed to retaining complete creative control as his business expanded. He refused to delegate.

‘I must be a part of it. I’ve never ever just leant my name for a commercial business venture.’

On the face of it, this was a good thing as it sustained quality through growth. But it also put incredible pressure on the man himself. He was overworked and stressed, tired and prone to panic attacks. Increasingly he turned to drugs to sustain him. He became a bully in the workplace, an aloof presence behind his signature black sunglasses. Deadlines slipped.

‘It’s like quicksand. If everyone around you is going down, you’re going to go down too.’

Pat Cleveland, Model

The Decline and Fall

In 1983 Norton Simon was sold to Esmark, an even bigger conglomerate that included Playtex. Senior executives were immediately concerned by the wasteful practices and creative extravagances at Halston.

‘I’m at the top and I don’t care what’s happening in the engine-room. I know the engine-room isn’t running. And it wasn’t. Turn this into a brand. Turn this into something we can handle and stop having it be this airy fairy kind of ‘work when I want to, I’m not inspired, I’m an artist’ kind of thing.’

Walter Bregman, Playtex President

Halston’s MD took to placing ‘to-do’ notes on his desk every day. The relationship deteriorated. Halston came into work later and later. When at length he talked about leaving Esmark and starting out on his own again, he was quickly put back in his box.

‘You don’t own your own name, pal. Read the small print. We own your name.’

Walter Bregman, Playtex President

By this time Halston’s star was on the wane. Soon he was eclipsed by Calvin Klein and a new generation in fashion. In 1984 Halston was locked out of Olympic Tower, and a junior designer was given his role as creative director. Esmark sold off his samples and wiped all the tapes of his shows.

Halston retired to San Francisco and became a recluse. In 1990 he died of AIDS-related lung cancer, one month short of his 58th birthday. It was a sad and untimely end for a hugely talented and influential man.

We always think a strong brand can comfortably extend into other areas of life. And often it can. And it goes on extending. And on and on. Until the elastic snaps.

'I'm in with the "in” crowd.

I go where the "in" crowd goes.

I'm in with the "in” crowd.

And I know what the "in" crowd knows.

I'm in with the "in” crowd.

I know every latest dance.

When you're in with "in" crowd

It's easy to find romance.’

Bryan Ferry, ’The ‘’In’’ Crowd (B Page)

No. 249