Paule Vézelay: No One Is a Prophet in Their Own Land

Vézelay’s oil-on-canvas Growing Forms (1946)

‘Art develops. The more you think about it, the more it changes.’

Paule Vézelay

I recently visited a splendid exhibition of the work of Paule Vézelay (The RWA, Bristol until 27 April), and supplemented it by watching a compelling 1984 interview with the artist by Germaine Greer (BBC, Women of Our Century).

‘What is important is the work. Is it original? Is it well done? Is it good?’

Vezelay was one of the first British painters of abstract art. She created joyous works inspired by natural forms. She experimented with shadows, silhouettes, colours, curves and movement. And, above all, she conjured up ‘living lines.’

‘After much study, practice and thought, I began to hope that, whether painted or drawn, my lines were ‘living lines’… and in my most optimistic moments I was content, feeling that these lines did indeed come from my hand and my Spirit…that they were inevitable.’

Born Marjorie Watson-Williams in Bristol in 1892, the daughter of a surgeon, Vézelay studied at the Bristol School of Art and, briefly, at the Slade School of Fine Art.

‘I’d already studied in art school for two years, and I didn’t want to be treated as a beginner at the Slade. They were very old fashioned, I thought… And I was bored to death.’

Paule Vézelay, Silhouettes, 1938. Photo England & Co ©Estate of Paule Vézelay

Vézelay’s early output was figurative. She had an eye for observing people and a fascination with the theatre. All was to change when she visited Paris in 1921. She was stunned by the quality of the art she found in the galleries and suddenly England seemed terribly provincial.

‘There wasn’t anything outstanding to my mind at that time in England.’

In 1926 Vézelay moved to France on her own, to forge a new life and embark on a radical transformation of her work. Marking this new chapter, she adopted the name Paule Vézelay, ‘for purely aesthetic reasons.’

‘I’ve never pretended to be a man. Never… It certainly would have been easier for me as an artist if I had been a man.’

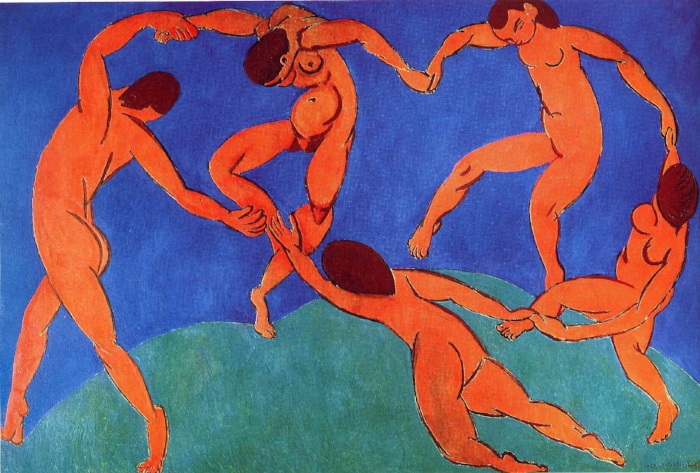

Vézelay dived headlong into the French capital’s artistic life. She became part of a circle that included Picasso, Matisse, Calder, Kandinsky and Miro. Abandoning figurative painting, she adopted abstraction and joined the Abstraction-Création movement. And she fell in love, with fellow artist André Masson, living and working with him for four years. Their engagement however was called off.

‘Unfortunately – or fortunately – I had reason to change my mind. And I changed it, which was very painful.’

She remained unmarried for the rest of her life.

Paule Vézelay pictured circa 1919. Photograph: Estate of Paule Vézelay/RWA

Vézelay’s art is full of floating biomorphic shapes, bright optimistic colours, airy spaces and sensuous, serpentine lines.

‘[Curves] exist in nature and they exist in life. Why limit yourself to straight lines and angles?’

She sought to make work which lifts the spirit.

‘I dislike sad art. There’s enough real sadness in real life. I think an artist might create something joyful or happy or pleasing.’

Vézelay was always curious to try new things. She experimented with three dimensional pictures that featured threads or wires strung across the picture frame and hung in shallow boxes.

‘You’ve got to do a lot of thinking before you invent something which is rather new.’

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Vézelay moved, reluctantly, back to Bristol, where she served in the Home Guard and cared for her elderly mother. She also set about drawing bomb damaged buildings and barrage balloons (what she called ‘tough monsters’). And all the while she continued to produce abstract paintings.

‘A line’s very extraordinary. It can be dark or light or curved or straight. And it can be a lively line, a dull line. But you’ve got to be able to control it with your hand, and that takes years of practice.’

After the war Vézelay had difficulty gaining recognition from England’s conservative art establishment. Nevertheless, she persisted.

‘I start work at my easel and I know it’s bad, know it’s quite bad. But I think it’ll lead onto something better. So I go on. And I can always tear up the bad work I’ve done. It often does lead to something more complete and better. Bad work can lead to good work.’

Relief sculptures … Lines in Space No 51 (1965). Photograph: © The Estate of Paule Vézelay

In the 1950s, to supplement her modest income, Vézelay designed textiles for Metz & Co of Amsterdam and Heal's of London.

‘I have a certain amount of faith in myself, confidence in myself.’

Vézelay exhibited occasionally and sold some of her pieces. But for the most part, not given to self-promotion, she remained outside the public eye. As Greer observed in the 1984 interview:

‘Her work is her life, and she keeps it about her as a living oyster keeps its pearl.’

In the interview we see an elderly Vézelay at home. She wears a smart silver necklace, has neat grey hair and a benign smile, listening patiently, replying precisely.

‘I like my work, strange as it may seem. I like my paintings. I like to keep them. I’m never in a hurry to sell them.’

She emerges as a self-possessed, intelligent woman, with a steely determination to make up her own mind and forge her own path.

‘To draw a line is very difficult. It takes years before you can draw the exact line you want in the exact way, in the exact place that you want it to be.’

The story of Paule Vézelay reminds us of the Biblical aphorism:

‘A prophet is not without honour, except in his own country, among his own relatives, and in his own house.’

Mark 6:4

Sometimes we are not properly appreciated by our friends, family and colleagues. Sometimes we must leave our home, our town, our country, our workplace, in order to break free from limiting assumptions and constraining conventions; in order to establish our own way in the world.

The Tate finally gave Vézelay a retrospective exhibition in 1983. She died the following year, aged 91.

Greer: Would you say that yours has been a happy life?

Vezelay: I don’t know what you mean by happy. I did what I wanted to do. I wasn’t obliged to go and work as a typist in an office, or as a saleswoman, or as a children’s nurse. I’ve been very fortunate.

'When you're running out

And you hear them coming like an army loud.

No time for packing,

When you're running out.

You fall to the ground

But you're holding on.

Is this called home?

Land turns to dust,

This can't be home,

Time's running out for us.’

Lucy Rose, ‘Is This Called Home?’ (L R Parton)

No. 512