Our Redacted Lives: Why Don’t We Take Our Whole Selves to Work?

‘The mind is like an iceberg. It floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.’

I recently visited the last home of Sigmund Freud (The Freud Museum, Hampstead). Fleeing from Nazi Austria in 1938, the elderly Freud settled in an airy, spacious Hampstead villa, not far from the Finchley Road. He lived there for little over a year - long enough to accustom himself to British life.

‘It is bitterly cold, the plumbing has frozen up and British deficiencies in overcoming the heating problem are clearly evident.’

Freud managed to take with him to Hampstead many of his possessions from Vienna, and he was able to recreate his study and consulting room in his new home. After his death, his daughter Anna preserved things as he left them.

The study is lined with books and filled with Freud’s collection of Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Oriental artefacts. Busts, masks and figurines queue up in ranks along the cluttered desk and shelves. He was fascinated with antiquities and regarded himself as an archaeologist of the mind.

‘The psychoanalyst, like the archaeologist in his excavations, must uncover layer after layer of the patient’s psyche, before coming to the deepest, most valuable treasures.’

Not far from Freud’s desk resides his original analytic couch, covered in red patterned rugs and reputed to be very comfortable. To one side, behind where the patient’s head would rest, we see the chair in which Freud would sit, prompting, listening, thinking.

‘The ego is not master in its own house.’

Freud believed that human behaviour is largely driven by unconscious motivations deriving from childhood experiences; that the sublimation of these instinctual urges of love, loss, sexuality and death creates neuroses; and that the unconscious can be revealed in dreams and unguarded moments.

‘Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.’

During the First World War the Viennese newspapers had often been censored and Freud used the metaphor of censorship to explain the way the conscious mind actively suppresses the unconscious.

I was quite struck by the thought of self-censorship in its broadest sense. I’m sure it’s true that we keep a lid on our deepest desires and anxieties for fear of shame, opprobrium, public disapproval; in order to protect ourselves. We are unreliable narrators. We suppress inconvenient truths. We live redacted lives.

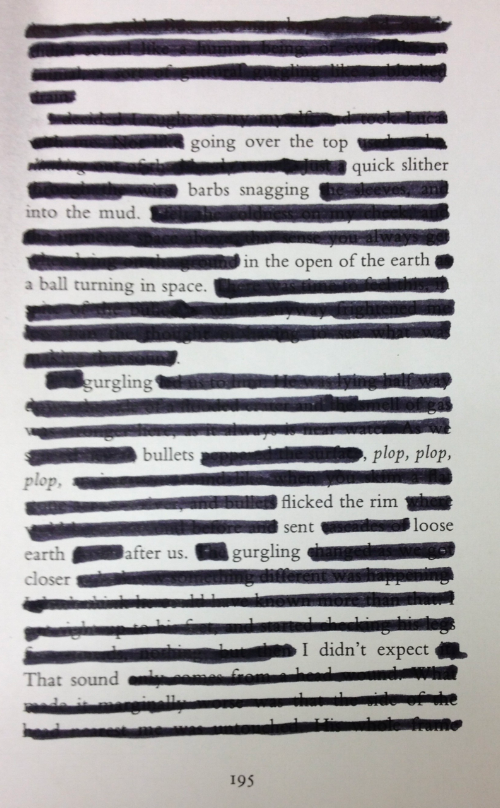

Example of redacted poetry from the Scottish Poetry Library (using a page from Pat Barker’s ‘The Ghost Road’)

I suspect self-censorship extends to the workplace too. In the office we are more guarded, reserved and cautious about revealing our true selves. We present an edited identity to our colleagues, one which we feel will fit in with the norms of the profession, the company culture and the boss’s expectations.

A young intern came to chat to me in the last week of her time at the Agency. She was studying communication at a college by the Elephant. She seemed intelligent, nice, polite, but not particularly out of the ordinary. We had a twenty-minute chat and she was about to go. She paused.

’Can I ask you one last question? I’ve not mentioned that I’ve been designing and selling my own fashion range online. I didn’t say anything about it before because I thought it might suggest I wasn’t dedicated to advertising. Was I right not to mention it?’

‘Not at all. It’s completely relevant. Tell me more.’

‘Well, my designs have a Somali flavour. I came over here as a refugee when I was 5 and had to learn English from scratch. I want my clothes to express my birth-culture, even though I only have vague memories of it.’

Suddenly an ordinary woman demonstrated that she was extraordinary; that she had life experiences and achievements that few in our industry could match. And yet she had been hesitating to reveal these things because she thought they might not be relevant.

I was touched, but also troubled by the realisation that this woman was in many ways typical. What was particularly frustrating was that as an employer you learn to value originality over orthodoxy; authenticity over affectation. You yearn for idiosyncrasy, individuality and independence, because these are the characteristics that drive culture and innovation.

‘Out of your vulnerabilities will come your strength.’

In an ever more automated world a company’s competitive difference is increasingly determined by its ability to realise the full value of its human capital: expressing all talents, articulating whole selves. This is not just a challenge for leaders. It’s something every individual should address.

How often do we present moderated, edited, diluted selves to our colleagues? How often do we suppress the passions and personality traits that may in fact be most useful to the business? Why can’t we take our whole selves to work?

If we can’t answer these questions, then I fear our redacted lives will inevitably become redacted careers.

No. 127