Space Is the Place: Nostalgia for the Future

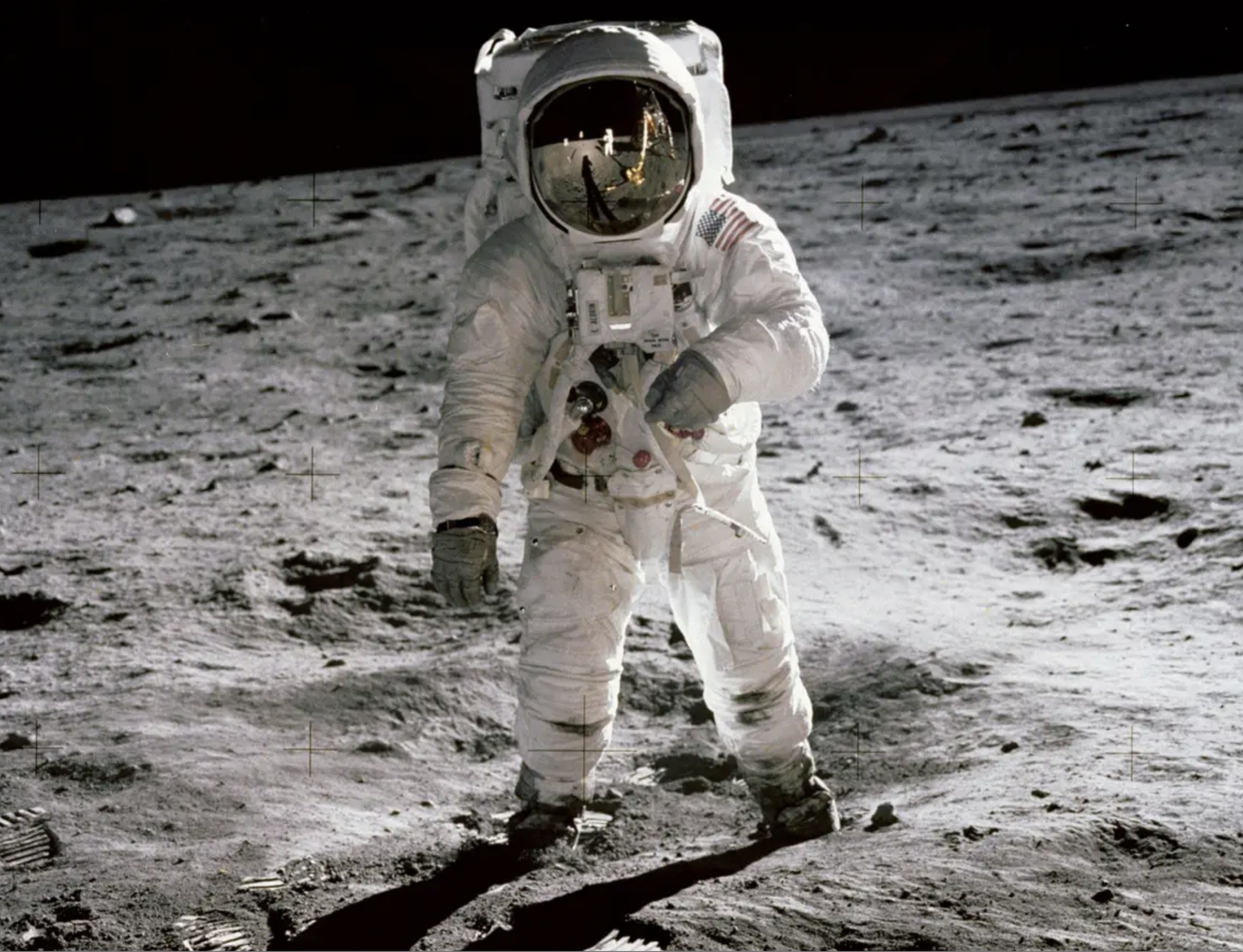

'Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.'

I know exactly where I was just before 4-00AM on the morning of July 21, 1969. I was in the sitting room of 125 Heath Park Road watching TV. My parents had got Martin and me out of bed to see Neil Armstrong become the first person to set foot on the moon. I was 5 years old.

To be honest I’m not sure I recall the experience. Perhaps I just remember being told that I was there. But certainly rockets, space exploration and moon landings played an important part in my childhood. Back then we dreamed of astronauts, aliens and asteroids. We watched Star Trek, the Clangers and Thunderbirds on TV. We created space suits out of boxes and Bacofoil. And one summer Sister Mary Stephen helped me make a lunar landscape out of papier mache.

Armstrong: 'The surface is fine and powdery. I can kick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the sole and sides of my boots.’

Over the last few weeks there have been numerous documentaries and dramas commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the first lunar landing. I was particularly struck by the film ‘Apollo 11’, which edited together original footage from NASA and the National Archives.

The crowd at Cape Canaveral wait expectantly in sun visors and straw trilbies. The women sport cat-eye shades. Families in striped summer shirts camp out on the parking lot at JC Penney’s. Wide-angled lenses are trained and at the ready. At Mission Control Center in Houston banks of clean-cut men in headsets attend to their monitors. They wear white short-sleeved shirts, thin ties and have pens in pocket protectors. Their desks are cluttered with coffee cups and ashtrays. After a steak-and-egg breakfast, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins complete their final checks and wave goodbye. Then the unbearable tension of the countdown...

‘12, 11, 10, 9, ignition sequence start.’

Time slows to a crawl…

‘6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, zero, all engines running.’

The thunderous roar, the fearsome commotion, as the Saturn V rocket escapes its umbilical tower, and takes off…

‘Liftoff! We have a liftoff, 32 minutes past the hour. Liftoff on Apollo 11.'

It’s a familiar drama now, but it still sends a chill down my spine.

Collins: 'Well, I promise to let you know if I stop breathing.’

As the adventure continues, I can’t help being struck by the dry, understated humour of these brave, intelligent men. I fell in love with the United States in 1969, with this casual heroism, this easygoing informality.

Aldrin: 'Now I want to back up and partially close the hatch... Making sure not to lock it on my way out.’

For me as a child the space program was entirely optimistic, inspiring, euphoric. It was a compelling tale of vision, ambition, ingenuity and courage. The stainless steel plaque attached to the ladders of the lunar module stated: ‘We came in peace for all mankind.' And President Nixon, speaking on the phone to Armstrong and Aldrin while they were on the moon surface, intoned in his rich, gravelly voice:

'For one priceless moment in the whole history of man all the people on this Earth are truly one.'

There seemed something noble and uplifting about the whole endeavour.

Of course, looking at the flickering footage now, one can’t help noticing the shadow that the Eagle module cast over the moon’s surface. And there was a shadow over the space program too.

There were protests about the US Government’s priorities at a time when the country was facing incredible poverty and inequality. At its peak in 1966, NASA accounted for roughly 4.4% of the federal budget. The resonance of Nixon’s words now seems tarnished by Vietnam and Watergate, and there’s a suspicion that we were simply witnessing another chapter of the Cold War. We also feel uncomfortable about the low representation of female and black faces at Mission Control; and the debris left on the lunar surface.

Armstrong: 'Isn’t that something! Magnificent sight out here.'

Aldrin: 'Magnificent desolation.’

Nowadays the future has lost some of its lustre. Although we’ve witnessed the most dramatic transformation since the Industrial Revolution, we have become concerned that the same technology that spreads knowledge and understanding can also intensify hate and bigotry; that a new corporate oligarchy threatens our privacy and security; that the freedoms of empowerment also carry the responsibilities of self-control. Inevitably we’re suffering change fatigue.

Aldrin: 'We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown.'

Despite the reservations, the Apollo 11 story prompts nostalgia for the future. It suggests that hope and optimism are the first steps to progress. It reminds us of the power of wide-eyed anticipation. We should not deny ourselves the chance to dream.

'I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.'

President Kennedy, May 25, 1961

The US space program remains the definitive example of the motivational power of a clear and ambitious goal. It indicates that we can achieve great things if we channel talent and resource towards a unitary mission, if we commit to the principles of focus and weight.

Imagine reconvening those dudes in their thin ties and short-sleeved shirts. What if we could create the contemporary equivalent of Mission Control? What if we summoned a more diverse cross-section of the finest minds in the world, allocated proper investment, and set them a singular task? What if we asked them to save this planet rather than to visit some other celestial body?

Aldrin: 'There it is, it’s coming up!'

Collins: ‘What?'

Aldrin: 'The earth. See it?'

Collins: 'Yes. Beautiful.’

'Space is the place where I will go when I'm all alone

Space is the place,

Space is the place.’

Sun Ra, ’Space is the Place'

No. 241