The Enchanted Brand: What Can Magic Teach Marketing?

German magician Jacoby-Harms in an 1866 photograph by FA Dahlstrom using double exposure to create the illusion of objects floating in the air

‘Magic is the only honest profession. A magician promises to deceive you and he does.’

Karl Germain, Magician (1878-1959)

I recently attended an excellent exhibition about the psychology of magic (’Smoke and Mirrors’ at the Wellcome Collection, London, until 15 September), and read a fine accompanying book (‘The Spectacle of Illusion’ by Matthew L Tompkins).

Spiritualism gripped nineteenth and early twentieth century society. Celebrated mesmerists could manipulate magnetic life forces. Hypnotists could put people in a trance. Mediums could make the dead speak. Ghostly presences would rap out messages via dedicated wands. They would speak through spirit trumpets, write on slates, ring bells and play musical instruments. They made furniture float, supernatural limbs appear and ectoplasm ooze from random orifices.

The public fascination with the paranormal was enhanced by the ubiquity of disease and the escalating numbers of casualties created by modern warfare. Many attended séances in the hope of making contact with departed loved ones. Ouija boards became a popular parlour activity.

Spiritualism also spread to the new technology of photography. Deceased relatives appeared as ghostly presences on photographic slides. Mysterious body parts were observed alongside sitters. Phantoms could be seen haunting medieval churches and stately homes.

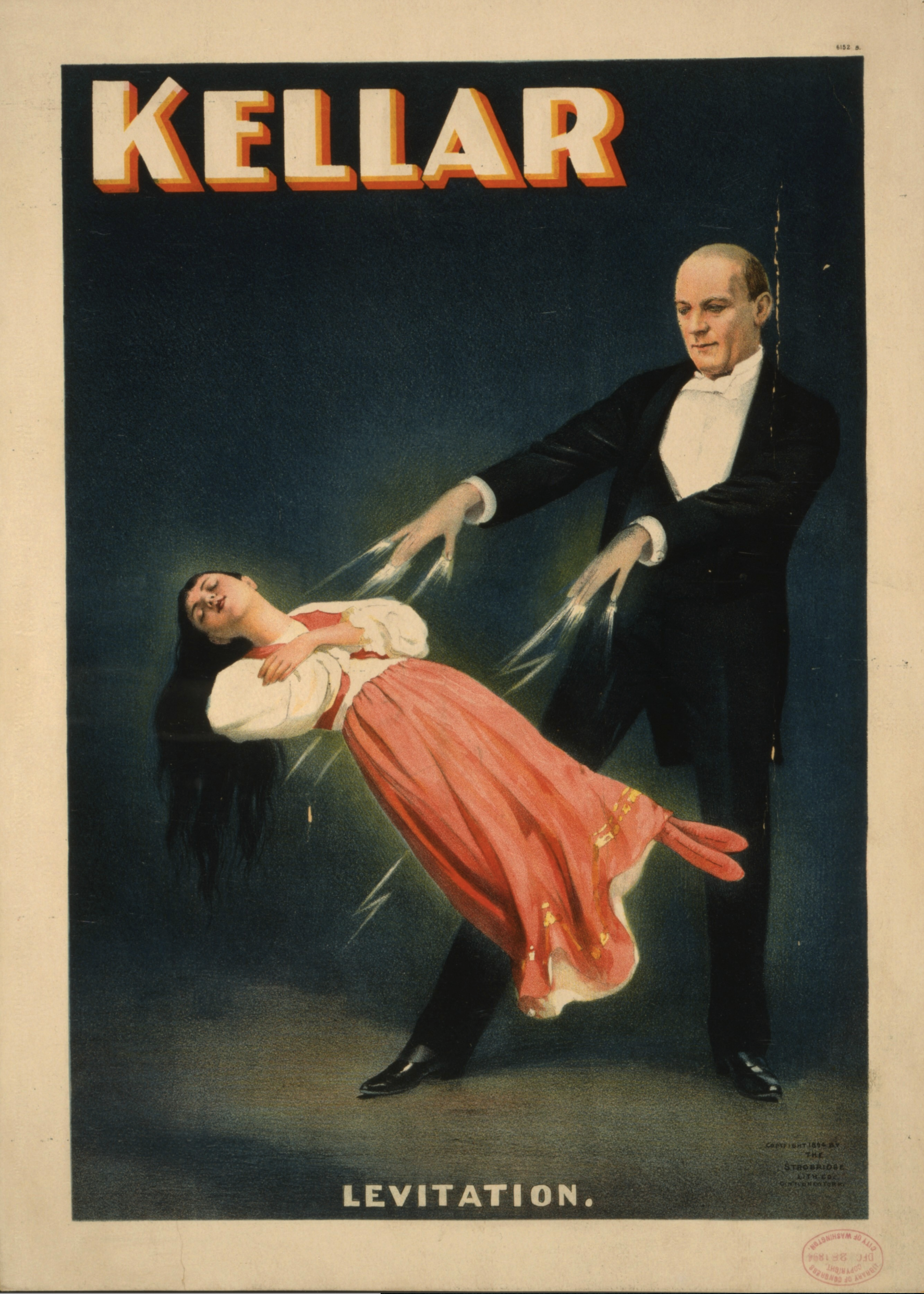

Commercial magicians, alert to the phenomenon, adopted and adapted the techniques of spiritualism and created hugely successful stage acts. Posters proclaimed that Mrs Daffodil Downey would perform public séances at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly; Harry Keller would make Princess Karnac levitate; and the automaton Psycho would play whist with audience members.

Inevitably scientists were keen to establish whether spiritualists were genuine, and in 1882 the Society for Psychical Research was set up specifically to examine the area. They constructed dedicated laboratories, designed special apparatus and organised complex experiments.

Often results were inconclusive, and expert opinion was divided. Some respected figures remained convinced of spiritualism’s authenticity.

‘The author has seen numerous photographs of the ectoplasmic flow from ’Margery’ [the medium Mina Crandon] and has no hesitation in saying that it is genuine.’

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1926

The problem for the more sceptical scientists was that their measurements and machines were often outwitted by the spiritualists’ tricks and techniques.

‘While scientists are trained in gathering evidence based on empirical observations, they are not necessarily trained in deception.’

Matthew L Tompkins, ‘The Spectacle of Illusion’

Consequently the scientists turned to commercial magicians for help. Magicians could draw on their knowledge of conjuring tricks and illusions to test the claims of the mediums and debunk the fraudulent. In one celebrated incident magician Harry Houdini prevented the medium Mina Crandon from collecting a reward by exposing her deceptions. It was an early success for interdisciplinary research.

‘[Spiritualism’s] worst evil has been the fostering of the unscientific spirit, the attempting to seek truth through the emotions rather than through the intellect.’

George Beard, Neurologist, 1879

What are we to make of the spiritualist phenomenon?

Well, it may all seem like distant history. But despite the advances of science since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there remain huge gaps in most people’s understanding of the physical world; and like our forefathers we tend to fill these gaps with assumptions and suppositions. We may insist that we are rational beings. But we are prone to believe what we feel, what we want, what we hope. And our senses are still not as reliable as we might imagine.

As marketers and communicators we should be ever mindful of the emotional component of decision-making. Indeed we should embrace the potential of the Enchanted Brand: a brand that beguiles, bewitches, charms and inspires; that is comfortable filling the space between the real and the imaginary.

We should also, like the sceptical scientists before us, learn to enlist expert witnesses from other disciplines to illuminate a category we do not fully understand.

There’s a compelling section of the exhibition that explains how the most important skill a magician has to learn is misdirection: drawing attention to one thing so that we are unaware of something else.

‘This idea of the hand being faster than the eye is completely wrong…Speed has nothing to do with it. It’s all attention control.’

Professor Ron Rensink, University of British Columbia, 2009

In a demonstration of ‘misdirection of perception’ (set up by psychologists from Goldsmiths, University of London), we watch a conjuror perform a trick with the trace from an eye tracker superimposed on the film. We see that the viewer’s gaze consistently fixes on the spot the magician wants, rather than the area where the deception is taking place. In a second demonstration, we see a conjuror employing ‘misdirection of memory’: we are encouraged to remember one card in a hand, and in so doing we fail to remember the others. Another demonstration illustrates ‘misdirection of reasoning’: we project from repeated similar experiences that that same experience will happen again, and therefore we imagine events that in fact never occur.

Of course, in the marketing and communications industry we would not subscribe to misdirection as a technique. We are, on the contrary, seeking to reveal truth and enhance it. However, in order to achieve enhanced truth, we often have to focus consumers’ minds. Indeed a strong brand actively endeavours to direct attention, reasoning and memory. It channels attention towards its greatest virtues; it establishes a narrative about its past that supports and sustains those virtues; it creates expectations of the future that become self-fulfilling. There are strong parallels between the disciplines.

There is one compelling theme that runs throughout the exhibition. Consistently we discover that believers are more open to suggestion than sceptics. They are more eager to please, more keen to have their convictions confirmed.

‘As a magician, I was able to see two things very clearly: a) how people can be fooled, and b) how they fooled themselves…The second is far more important.’

James Randi, Magician, 2007

Whilst not seeking to fool consumers, surely a primary responsibility of marketing is to build belief: to create a positive predisposition towards a brand such that claims are more favourably received and criticisms are more immediately rejected. Positive predisposition creates the context for a successful sale.

In a 1944 performance ‘the Amazing Dunninger, the Greatest Mental Marvel of the Age’ began with an announcement:

’I cannot invade against opposition. You must want me to get into your thoughts before I can. Do you want me in there?’

'If you believe in magic, come along with me.

We'll dance until morning 'til there's just you and me.

And maybe, if the music is right,

I'll meet you tomorrow, sort of late at night.

And we'll go dancing, baby, then you'll see,

How the magic's in the music and the music's in me.'

The Lovin’ Spoonful, 'Do You Believe in Magic' (John Sebastian)

No. 233