To See Ourselves As Others See Us

Cartier Bresson/Waiting in Trafalgar Square

‘O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae mony a blunder free us,

An' foolish notion:

What airs in dress an' gait wad lea'e us,

An' ev'n devotion!’

Robert Burns/ To a Louse

We are all engaged in observing the world around us. But how good are we at reflecting on ourselves? Do we ever truly see ourselves as others see us?

Strange and Familiar

Strange and Familiar, an exhibition currently running at the Barbican in London (until 19 June), showcases the ways that foreign photographers have regarded Britain from the 1930s to the present day.

Initially these non-British perspectives on Britain seem almost stereotypical. There are Bobbies, bowler hats and boozers; cafes, corner shops and carnivals. We come across queues in the rain, deckchairs on the beach, commuters in the fog. We find milk bottles, uniforms and lollipop ladies. The decades process past us to the familiar tune of fashion trends, political upheavals and State occasions. We canter through the Coronation celebrations, the Swinging Sixties, the Jubilee Street Parties, the Troubles. It’s a reminder that cliché is often founded on some truth.

But, on closer inspection, these outsiders make Britain look quite curious. The pageantry seems alien and exotic; the dirt and decay seem primitive. One is struck by the post-war weariness, the arcane folk rituals, the enduring class divide.

Seeing ourselves as others see us is, as the exhibition title suggests, a ‘strange and familiar’ experience. We recognize the reflection looking back at us from the mirror. But, with scrutiny, we also notice wrinkles, scars and blemishes that would generally elude us.

‘People think that they present themselves one way, but they cannot help but show something else as well. It’s impossible to have everything under control.’

Rineke Dijkstra, Photographer

This kind of introspection is bracing, refreshing, thought provoking. We get to see what the American photographer Diane Arbus called ‘the gap between intention and effect.’ So it’s perhaps something we should all do more of. However, I’m not sure it’s natural to welcome the outsider’s perspective.

When I was in advertising, we would always decline the opportunity to be filmed at work. It wasn’t that we were afraid of ‘letting daylight in upon magic.’ It was that we knew we would look like fools. We were well aware that the language and process, the acronyms and enthusiasms, all seem rather daft when you’re not in the midst of them. And sometimes the truth hurts.

Of course, in the broader marketing and comms world we do regularly canvas the opinion of consumers and colleagues, in focus groups and 360 degree appraisals. But how often do we embrace the perspectives of true outsiders on our brands, on our businesses, on ourselves? How often do we properly examine the distinctions between our own intentions and effects

Would we be shocked or reassured by what they saw and said? Or would we listen without hearing, look without seeing?

The Same, But Different

‘I wanted to make the series almost as a mirror in which to see myself.’

Hans Eijkelboom

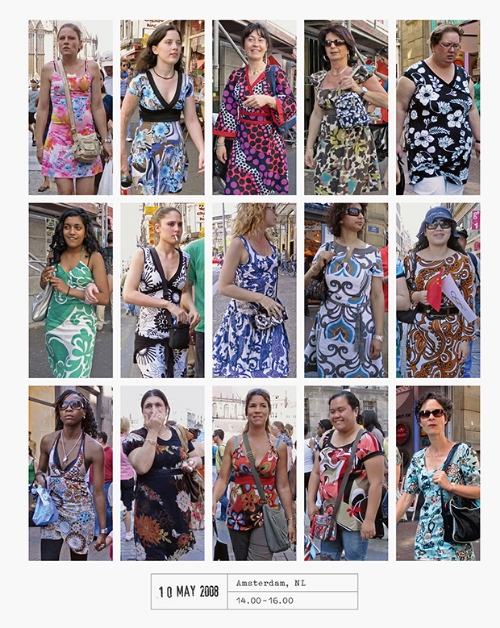

In the last room of the Barbican exhibition we encounter a film composed of photographs by the Dutch artist Hans Eijkelboom (The Street and Modern Life). In 2014 Eijkelboom shot people out and about in Birmingham’s Bullring shopping centre. He then reassembled the images in accordance with certain aspects of their appearance.

We see life played out in repetition and replication, a symphony of theme and variation.

There are sequences of floral designs, ripped jeans and crop tops; checks, stripes and polka dots; tattoos, beards and body piercing. There are Superdry sweats and Hollister hoodies. Headscarves. Women carrying Costa cups, handbags at their elbows, faces down to their phones; men in denim jackets, quilted jackets, sleeveless jackets. We see skull prints and Union Jacks; butterflies and Micky Mice. Adidas, Adidas, Adidas. Everlast.

It’s the rhythm of street style, the pattern of popular culture. There’s a compelling sense that, for all our individuality, we conform; for all our independence, we are interdependent; for all our difference, we are the same.

It’s a healthy reminder for the marketer. Ours has been an age of individuality and empowerment; of personalisation and customisation; of laser targeting and one-to-one. But we should never forget that fundamentally brands are shared behaviours and beliefs; that people like to copy, to swap, to emulate; to come and go and stay together; to think, and act, and be, together.

No. 77