Looking for the Heart of Saturday Night: The Imaginary World of Tom Waits

‘Well with buck shot eyes and a purple heart

I rolled down the national stroll

and with a big fat paycheck

strapped to my hip-sack

and a shore leave wristwatch underneath my sleeve

in a Hong Kong drizzle on Cuban heels

I rowed down the gutter to the Blood Bank

and I'd left all my papers on the Ticonderoga

and I was in bad need of a shave

and so I slopped at the corner on cold chow mein

and shot billiards with a midget

until the rain stopped

and I bought a long sleeved shirt

with horses on the front

and some gum and a lighter and a knife

and a new deck of cards (with girls on the back)

and I sat down and wrote a letter to my wife

’Tom Waits, ‘Shore Leave’

I recently watched a documentary on the musician Tom Waits (‘Tales from a Cracked Jukebox’, BBC4).

In his gruff, gravelly voice, Waits sings about loneliness and longing in the wee small hours; about outsiders and outcasts - lowlife at the liquor store, in cocktail bars, strip joints and tattoo parlours; about the one that got lucky and the one that got away; about dreaming to the twilight and drinking to forget; about forlorn lovers looking for the heart of Saturday night.

'Oh and the things you can’t remember tell the things you can’t forget

That history puts a saint

In every dream.’

‘Time’

Waits pores over the underbelly of American city life, telling tales of warped relationships and withered dreams, cracked aspirations and doomed love; the determined self-delusion of the hopeless case.

'Well I've lost my equilibrium and my car keys and my pride.’

‘The One That Got Away’

Waits is a master of characterisation. He gives us fragments from the lives of damaged veterans, worn out waitresses and escaped criminals - seen through the bottom of a beer glass; refracted through early morning tears. His stories are interwoven with incoherent conversations in a late-night drugstore, the elusive dreams of advertising, the insistent pitch of the whiskey preacher.

‘Don't you know there ain’t no devil,

There's just god when he's drunk.’

‘Heartattack and Vine’

Waits teaches us a good deal about the alchemy of storytelling; about drawing on a rich set of influences, infusing personal experience with invention and memory; about creating our own imaginary worlds.

Interviewer: Do you have a philosophy about writing?

Waits: Never sleep with a girl named Ruby and never play pool with a guy named Fats.

1. ‘Create Situations in Order to Write About Them’

Waits was born in 1949, in Pomona, California. His parents were teachers, his father an alcoholic. They separated when he was 10 and his mother took him to suburban San Diego. He dropped out of High School and did a variety of low-paid jobs.

‘It was a choice between entertainment and a career in air conditioning and refrigeration.’

Waits turned to music as an escape. He progressed from writing Dylan-influenced folk songs to jazz compositions inspired by the Great American Songbook. In 1972 he moved to LA, settled into a cluttered two-room apartment and hung out in the downtown bars, diners and pool halls.

‘You almost have to create situations in order to write about them, so I live in a constant state of self-imposed poverty.’

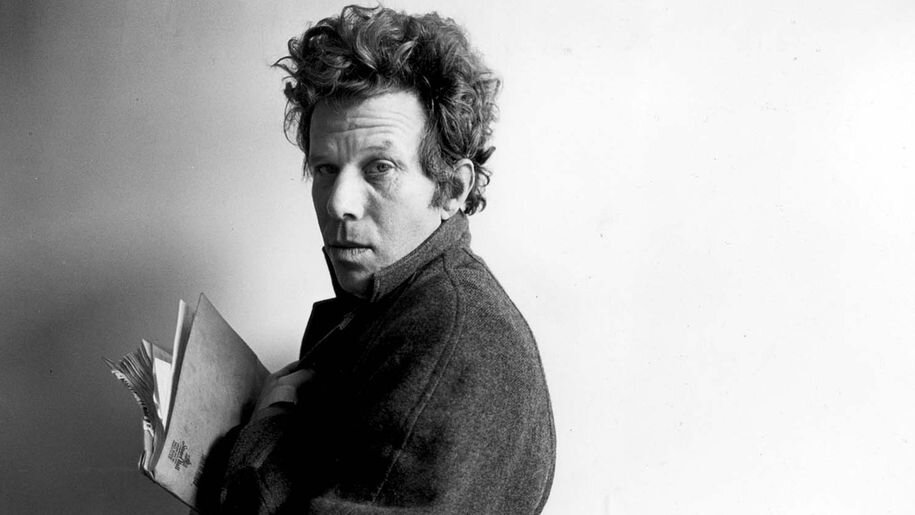

Album cover: Blue Valentine

2. ‘Combine Imagination with Experience and Memory’

'I like beautiful melodies telling me terrible things.’

Waits took notes of late night conversations with barflies and Bohemians; of dialogue overheard in taxis, at newsstands and gas stations. And then he set his imagination to work.

‘I remain in all of my stories, but at the same time I think that the creative process is a combination of imagination and experience and memories. By the time a story or song is finished, it may or may not resemble wherever the story came from.’

Importantly, Waits blurred the line between experience and invention.

'Mostly I straddle reality and the imagination. My reality needs imagination like a bulb needs a socket. My imagination needs reality like a blind man needs a cane.’

3. ‘Try to Discover That Which Has Been Overlooked By Moving Forward’

Waits grew up surrounded by the emerging hippie culture, but regarded himself as ‘a rebel against the rebels.’ He drew his inspiration from a previous age: from ‘50s Beat writers Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs; from film noir, Hitchcock and ‘The Twilight Zone’; from detective novels and the art of Edward Hopper. He was a man out of time.

‘Sometimes you find yourself going back in time just to locate something that you can’t find in the future. You’re trying to discover that which has been overlooked by moving forward.’

4. Write About People, Places and Things

Waits avoided hollow generalisations. He peppered his work with incidental details; with references to particular streets, brands and weather conditions – to Kentucky Avenue, Burma Shave and ‘that bloodshot moon in that burgundy sky.’ He always wrote about specific people, places and things.

'I think all songs should have weather in them. Names of towns and streets, and they should have a couple of sailors. I think those are just song prerequisites.’

Waits recognised that small events can create big dramas.

‘It’s the little things that drive men mad. It’s the broken shoe lace when there’s no time left that sends men completely out of their minds.’

5. Keep Evolving

Waits’ songwriting style changed over time.

'You have to keep busy. After all, no dog's ever pissed on a moving car.’

In the early ‘80s he became fascinated by Captain Beefheart, by the pioneering contemporary composer Harry Partch, and by Weimar artists Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. His song settings moved increasingly from the bar and diner to Vaudeville and the stage, the freakshow and the fairground. His writing explored themes of salvation and damnation. And his instrumentation embraced experimental brass, percussion and found objects

'Oh, I'm not a percussionist, I just like to hit things.’

6. ‘The Way You Affect Your Audience Is More Important than How Many of Them Are There’

'They say that I have no hits and that I'm difficult to work with. And they say that like it's a bad thing.’

Though Waits was much admired by critics and fellow artists, his commercial success was modest. Nonetheless he is regarded as one of America’s greatest songwriters. He has always focused, first and foremost, on the work.

'I would rather be a failure on my own terms than a success on someone else’s. That’s a difficult statement to live up to, but then I’ve always believed that the way you affect your audience is more important than how many of them are there.’

Waits reminds us that reward and recognition should not be objectives, but effects.

'I worry about a lot of things, but I don’t worry about achievements. I worry primarily about whether there are nightclubs in Heaven.’

The documentary left me reflecting particularly on the imperative for creative people to immerse themselves in incident and adventure. If we don’t expose ourselves to diverse people and rich experiences, how can we create compelling characters and original narratives? If we live conventional lives, how can we come up with unconventional ideas?

There is perhaps one other lesson suggested by Waits’ approach to creativity.

His vision is bleak, his themes are melancholy and his heroes are resolutely unheroic: the failing lounge singer, the desperate door-to-door salesman, the down-at-heel prostitute and the grubby private investigator.

'Most of the people I admire, they usually smell funny and don't get out much. It's true. Most of them are either dead or not feeling well.’

But these are real people with compelling stories. Waits has genuine empathy and at heart he is a romantic. He paints his pictures with respect and affection. And he always affords his characters a certain nobility.

'And I wondered how the same moon outside over this Chinatown fair

Could look down on Illinois

And find you there.’

‘Shore Leave’

'Wasted and wounded, it ain't what the moon did

Got what I paid for now.

See ya tomorrow, hey Frank can I borrow

A couple of bucks from you?

To go waltzing Mathilda, waltzing Mathilda

You'll go a-waltzing Mathilda with me.’

‘Tom Traubert's Blues’

No 301