Dressing for Yesterday: Seek Out the Social and Economic Jet Stream

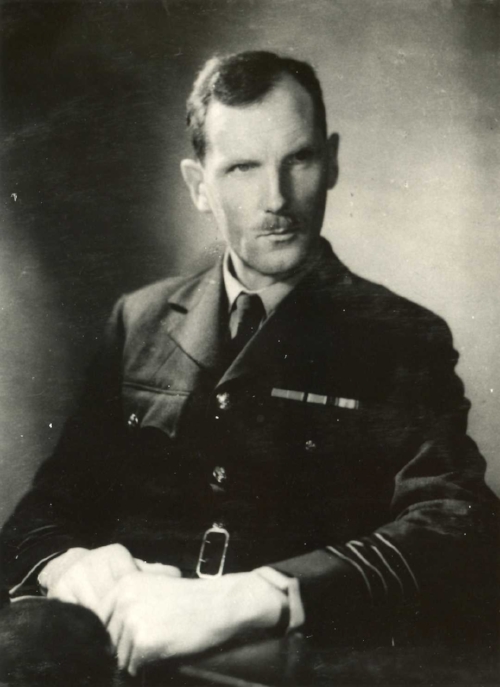

Group Captain James Stagg

‘Have you ever been to the beaches of Hastings, or Brighton, or Portsmouth? Ten o’clock in the morning it’s baking hot, the beach is packed. By midday, there’s a howling wind and the Punch and Judy man has packed up for the day. By two o’clock, the rain is horizontal, but by four o’clock the sun is beating down again and it’s eighty degrees. Nothing is predictable about British weather, that’s why we love to talk about it.’

Group Captain James Stagg, ‘Pressure’

I have an uncomfortable relationship with the weather. For some reason forecasts pass me by. Through the fog of getting up in the morning I rarely register what the bulletins are saying. They talk over and through me. And so my sartorial choices are driven by yesterday’s conditions. I assume a meteorological continuity that the British climate doesn’t warrant. And I find myself venturing into the searing heat in a tweed suit; into a cold snap with just a cotton smock; into the pouring rain without an umbrella. I always dress for yesterday.

Earlier this year I attended a fine play dedicated to the vicissitudes of the British climate. ‘Pressure’ by David Haig relates the story of Group Captain James Stagg, the Chief Meteorological Officer for the Allied Forces, who in June 1944 was responsible for forecasting the weather on D-Day.

The fleet is assembled along the South Coast. The tides, times and phases of the moon are appropriately aligned on only a few days each month, and General Eisenhower has allocated the 5th of June for the largest amphibious invasion in history. As the big day approaches, Stagg and his American counterpart, Colonel Irving Krick, are required to give a definitive meteorological assessment. 350,000 lives depend on them making the right call.

Krick employs the conventional method of forecasting: he revisits the charts from previous years where conditions were similar, and establishes analogues. He is confident that the weather will be fine.

‘The proof is in the past. I anticipate calm seas and clear skies on Monday – perfect conditions for the Normandy landings.’

Stagg disagrees. Sensitive to the temperamental British climate, he urges Krick to think beyond historical analogues; to take into account other factors; to think ‘three dimensionally’. He is a meteorological pioneer and he has recently discovered the jet stream. He predicts severe weather.

‘My forecast is not only based on weather at the surface. I’ve considered upper air-currents within the troposphere, at the tropopause, and in the lower stratosphere…The most powerful of these currents, measured two hours ago at twenty-eight thousand feet, is three hundred miles wide and three miles deep. I’ll refer to it as the jet stream.’

Stagg explains that the jet stream is prompting storms to move more rapidly than the surface charts would imply, and so severe conditions can be expected in the Channel on 5th June.

Ultimately Stagg persuades Eisenhower to delay the invasion by a day. He is right. There are high winds, heavy seas and low cloud on 5th June; but there is sufficient good weather on the 6th to make the Normandy landings a success.

It struck me watching the play that much of modern strategy is driven by the type of historical analogues on which Krick depended. We love case studies, precedents and best demonstrated practice. We cling to models and algorithms that anticipate tomorrow on the basis of yesterday; that predict the future on the basis of the past. Ten years on from the global financial crash, this remains the case.

Stagg teaches us to lift our eyes from the rear view mirror and think three dimensionally. The best strategists have foresight, an instinct for change, a curiosity about the evolving factors that might precipitate events. They seek the social and economic jet streams that are driving outcomes from high up in the stratosphere.

They don’t dress for yesterday. They dress for today.

‘Look out, kid.

Don't matter what you did.

Walk on your tip toes,

Don't tie no bows.

Better stay away from those

That carry around a fire hose.

Keep a clean nose,

Watch the plainclothes.

You don't need a weather man

To know which way the wind blows.’

Bob Dylan, 'Subterranean Homesick Blues'

In memory of Charlie Robertson, my first Planning Head at BBH. Funny, sharp, considerate and inspiring, he was everything you’d want from a strategist and leader. And he didn’t need a weather man to know which way the wind was blowing.

RIP Charlie Robertson (1954 – 2018)

No. 202