The Change Conundrum: Why Is Organisational Change So Difficult?

We all want to change. As individuals we want to learn, experience and progress. We all want our businesses and institutions to change too. We want them to adapt to circumstances, to realise new opportunities, to embrace the future. If we can harness our organisation to one inspirational vision of the future; if we can communicate new attitudes and behaviours with compelling clarity, then the collective whole will advance as one. We will together ‘move forward into broad sunlit uplands.’ Simple, isn’t it?

So why is change so difficult? And why is organisational change particularly challenging?

There are many good answers to these questions. Inevitably individuals’ and institutions’ appetites for change are counterbalanced by equal and opposite forces of habit and inertia. Sometimes the vision of change painted by our leaders lacks clarity and distinctiveness. Sometimes it is not pursued with sufficient vigour and passion. And sometimes there are also huge challenges of communication, education and motivation.

In my experience there is another critical dimension to organisational transformation: How do we determine precisely what should change and what should stay the same? What is the appropriate pace, scale, phasing and direction of change? This for me is the Change Conundrum.

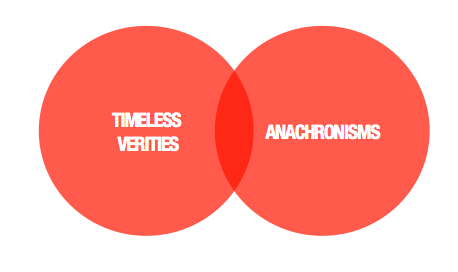

Within any business there are skills, disciplines and crafts that are, if you like, Timeless Verities: competences that are critical to the ongoing success of the enterprise, whatever the competitive or technological context. For a creative business these may be things like great art direction, copywriting, design; a robust strategic function; a rigorous production capability; meticulous relationship management. But there are also Anachronisms: processes, practices and approaches that have fallen out of step with the demands of modern life and commerce. When I first entered advertising, we would request four weeks to develop a press ad and six to script a TV commercial; design was the realm of blades, solvents, paste-ups and mechanicals; virtually everyone had an office and many people smoked in them.

Any progressive business should be seeking to rid itself of anachronistic practices, but it should also be seeking to sustain and develop timeless crafts and skills. The problem is that we can’t readily determine whether some processes and practices are Timeless Verities or Anachronisms. A few examples from my own sector: Should creatives continue to work in teams of two? Should they have an office to aid concentration? Should their department be separate or integrated with the rest of the Agency? Are these the critical ingredients of ongoing creative success or relics of a ‘pastime paradise’? I’ve heard it argued both ways.

Of course, whilst seeking to eradicate Anachronisms, the progressive business is also seeking to embrace new, liberating behaviours and beliefs; to take on new skill-sets and competences; to break out into new emergent space. But one could ask similar questions of our proposed new initiatives. At the outset they all promise Transformational Change. But some of them will inevitably end up representing Blind Alleys. So how do we separate one from the other?

Issues like these are at the heart of any change agenda. A progressive business seeks to identify the perfect balance between Timeless Verities and Transformational Change, eradicating Anachronisms and Blind Alleys along the way.

Over the years I found that the Change Conundrum applies as much to individuals as to skill-sets and processes. I’ve known quite a few colleagues who were dismissed as dinosaurs and deadbeats, only at a later date, and in some pressing crisis, to be celebrated as all-conquering heroes. Similarly people that were once welcomed as industry saviours could, with the passing of time, be exposed as snake-oil salesmen.

Organisational transformation is never simple or straightforward. It is always complex and confusing. Not least because it involves people’s careers and livelihoods. Of course, it’s much easier to position oneself as a radical: to suggest that change should always be root and branch; platforms should always burn; categories should always be killed. Total revolutionaries make the best speeches. But I was generally suspicious of Pol Pot-style purges of traditional crafts. Successful organisational change, at scale, is just more complicated than the rhetoric suggests. The stone that the builders rejected should sometimes become the cornerstone. And vice versa. And that’s the Change Conundrum.

‘What was wrong with me,

Was that I had to see,

All of the changes I put you through.

So now I’m changing for you.

Changing, girl.

Changing for you.’

The Chi-Lites, Changing for You

No. 90