The Graduate: ‘It's Like I Was Playing Some Kind of Game, But the Rules Don't Make Any Sense to Me’

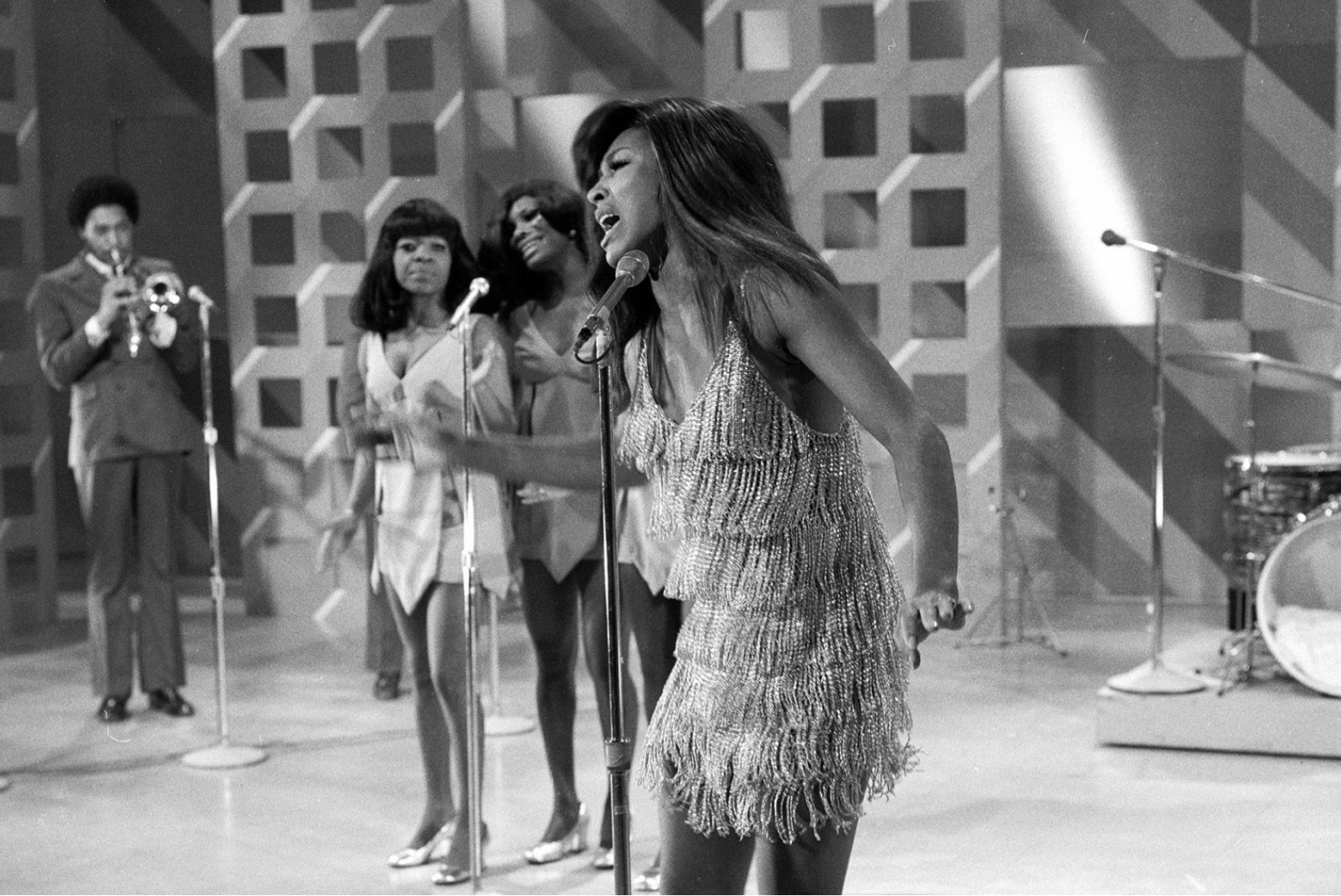

Anne Bancroft and Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate 1967

Mrs. Robinson: Do you find me undesirable?

Benjamin: Oh no, Mrs. Robinson. I think, I think you're the most attractive of all my parents' friends. I mean that.

‘The Graduate’ is a 1967 movie that stars Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock, a college graduate who is uncertain about his future. He feels distant from the values and aspirations of his parents’ generation, and yet he’s not sure what he’s doing or where he’s going. It’s a film about alienation and ennui. And it still resonates today, as young people endeavour to preserve a sense of identity and independence in the face of convention and tradition; materialism and the need to make a living.

'Ladies and gentlemen, we are about to begin our descent into Los Angeles. The sound you just heard is the landing gear locking into place. Los Angeles' weather is clear, temperature is 72.'

‘The Graduate’ opens with 21 year-old Benjamin on a plane home to Los Angeles, returning from college in the east. The credits roll and we hear the haunting harmonies of Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘The Sound of Silence.’

‘And in the naked light I saw ten thousand people, maybe more.

People talking without speaking, people hearing without listening.

People writing songs that voices never shared, no one dared disturb the sound of silence.’

Simon & Garfunkel, ‘The Sound of Silence.’ (P Simon)

With neat hair and wearing a suit and tie, Benjamin looks nervous, reflective, a little confused, as he stands on the travelator at LAX, passing white-tiled walls, accompanied by a repeated safety announcement.

‘Please hold the handrail and stand to the right. If you wish to pass, please do so on the left.’

He retrieves his single suitcase from the luggage carousel and exits the airport. Next we see him in his upstairs bedroom at his parents’ smart Pasadena home. Lying with his head next to the aquarium tank, he stares blankly ahead. Downstairs his parents and their friends have gathered to celebrate his graduation. His father comes up to chivvy him along.

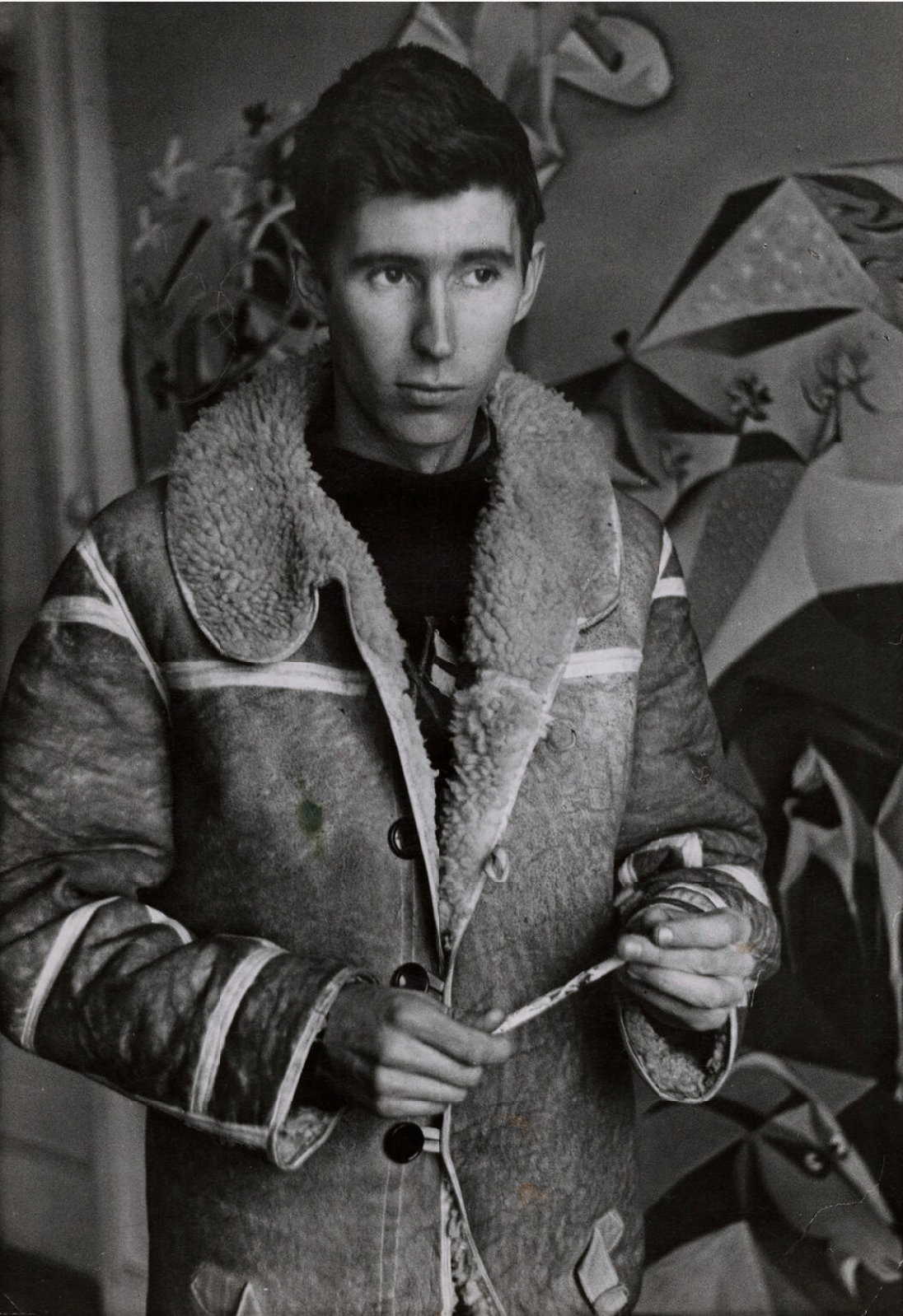

Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate. Photo Courtesy of Embassy Pictures

Mr. Braddock: Hey. What's the matter? The guests are all downstairs, Ben, waiting to see you.

Benjamin: Look, Dad, could you explain to them that I have to be alone for a while?

Mr. Braddock: These are all our good friends, Ben. Most of them have known you since, well, practically since you were born. What is it, Ben?

Benjamin: I'm just...

Mr. Braddock: Worried?

Benjamin: Well...

Mr. Braddock: About what?

Benjamin: I guess about my future.

Mr. Braddock: What about it?

Benjamin: I don't know... I want it to be...

Mr. Braddock: To be what?

Benjamin: ... Different.

Eventually Benjamin sallies forth and is greeted with a series of congratulations, pats on the back and affectionate kisses. A middle-aged man puts his arm over his shoulder and takes him to one side.

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Benjamin: Yes, sir.

Mr. McGuire: Are you listening?

Benjamin: Yes, I am.

Mr. McGuire: Plastics.

Benjamin: Exactly how do you mean?

Mr. McGuire: There's a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?

All at sea, Benjamin embarks on an affair with one of his parents’ friends. Mrs Robinson (played by Anne Bancroft) is glamorous, confident and droll. She is also bored, depressed and drinking too much.

Benjamin: For God's sake, Mrs. Robinson. Here we are. You got me into your house. You give me a drink. You put on music. Now you start opening up your personal life to me and tell me your husband won't be home for hours.

Mrs. Robinson: So?

Benjamin: Mrs. Robinson, you're trying to seduce me!

We learn that when she was Benjamin’s age, Mrs Robinson had studied art at college. But having become pregnant by her student boyfriend, she found herself married and sentenced to a life of affluent tedium. And her cultural interests seemed suddenly entirely irrelevant.

Benjamin spends the summer drifting: secretly meeting Mrs Robinson in a bedroom at the Taft Hotel; driving around town in his red convertible Alfa Romeo Spider; floating on a lilo in his parents’ pool, an Olympia beer at his side.

His father tries to rouse him to action.

Mr. Braddock: Ben, what are you doing?

Benjamin: Well, I would say that I'm just drifting. Here in the pool.

Mr. Braddock: Why?

Benjamin: Well, it's very comfortable just to drift here.

Mr. Braddock: Have you thought about graduate school?

Benjamin: No.

Mr. Braddock: Would you mind telling me then what those four years of college were for? What was the point of all that hard work?

Benjamin: You got me.

‘The Graduate’ is a fine movie: beautifully shot and crisply cut; wittily scripted and evocatively soundtracked. It established Hoffman as a star and director Mike Nichols as a new creative voice. It also gave us Anne Bancroft’s splendid portrayal of Mrs Robinson, a lost soul.

We may recognise in Benjamin’s delusion and apathy something from our own youth: the concern that society’s values do not chime with ours; the discovery that the commercial and corporate worlds have little in common with the high-minded realms of academia; the fear that there are no fulfilling roles and opportunities available to us.

‘It's like I was playing some kind of game, but the rules don't make any sense to me. They're being made up by all the wrong people. I mean no one makes them up. They seem to make themselves up.’

Benjamin’s dilemma presents a challenge to present day leaders in the world of work: How do we motivate and inspire new generations? How do we give them a voice, recognise their difference and individuality? How do we convince them that it’s a game worth playing?

In the event Benjamin finds motivation and meaning when he falls in love with Mrs Robinson’s daughter, Elaine – a development that naturally precipitates complications.

At the film’s climax Benjamin dramatically persuades Elaine to leave her new, conventional, parent-approved husband standing at the altar. As she runs down the aisle past the aghast congregation, still in her wedding dress, she is confronted by her mother.

Mrs. Robinson: Elaine, it's too late!

Elaine: Not for me!

'And here's to you, Mrs. Robinson,

Jesus loves you more than you will know.

Whoa, whoa, whoa.

God bless you, please, Mrs. Robinson,

Heaven holds a place for those who pray.

Hey, hey, hey.

Hey, hey, hey.’

Simon & Garfunkel, 'Mrs. Robinson’ (P Simon)

No. 454