NDT1: Locations Can Be Characters in Their Own Right

La Ruta ©Rahi Rezvani 2022 for Nederlands Dans Theater

'Someone walks alone/cutting the night into fragments of roads

The night is wounded/ bleeding through the cracks of a dream

Wounds scatter/ the breath of animals asleep/ the perfume of lilies

Eyes close and open/ night remains night’

Gabriela Carrizo

A little while ago I saw a programme of dance by the Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT 1 at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London). It was an evening of fierce athleticism, radical movement and provocative ideas.

I was particularly taken with a piece directed by Argentine choreographer Gabriela Carrizo.

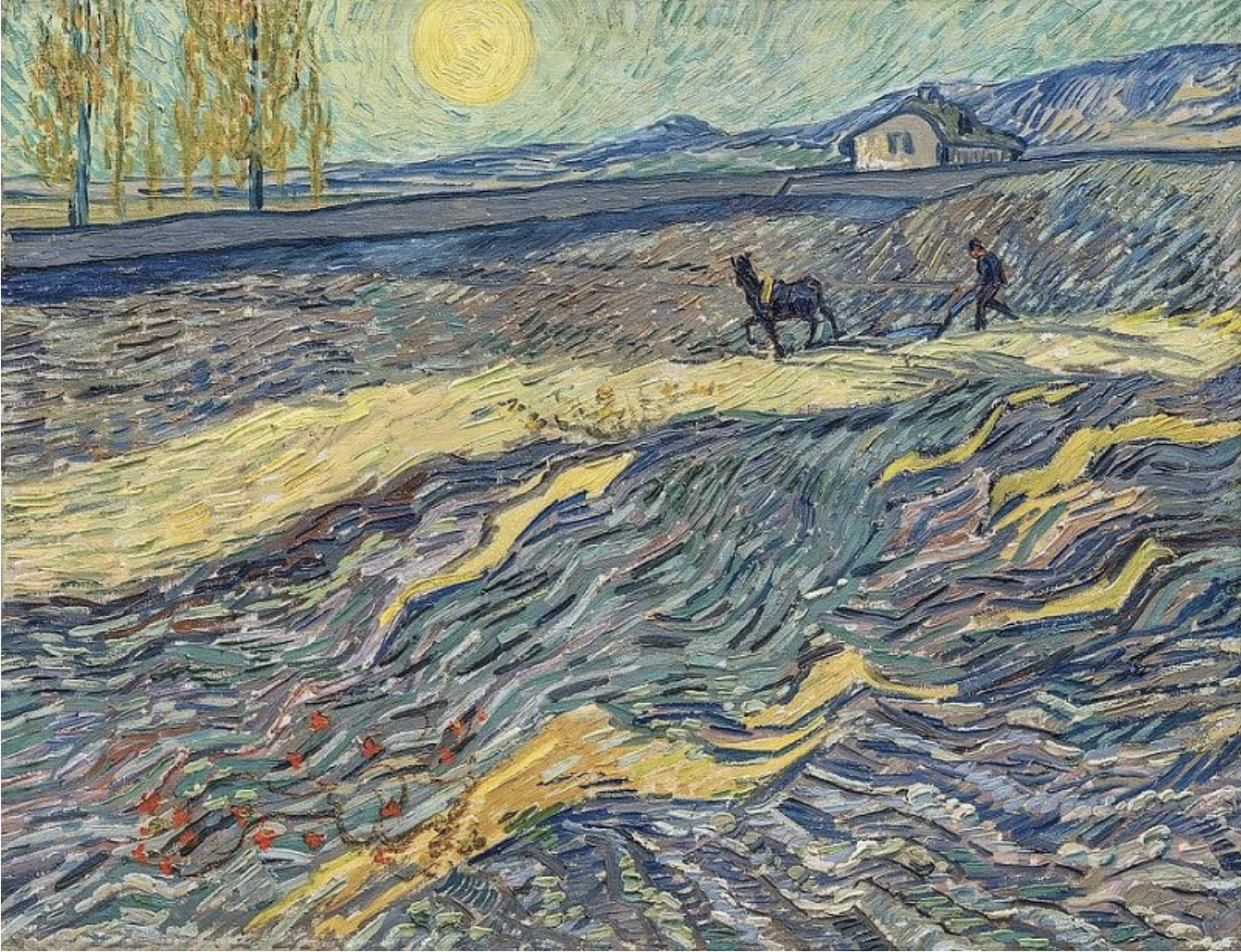

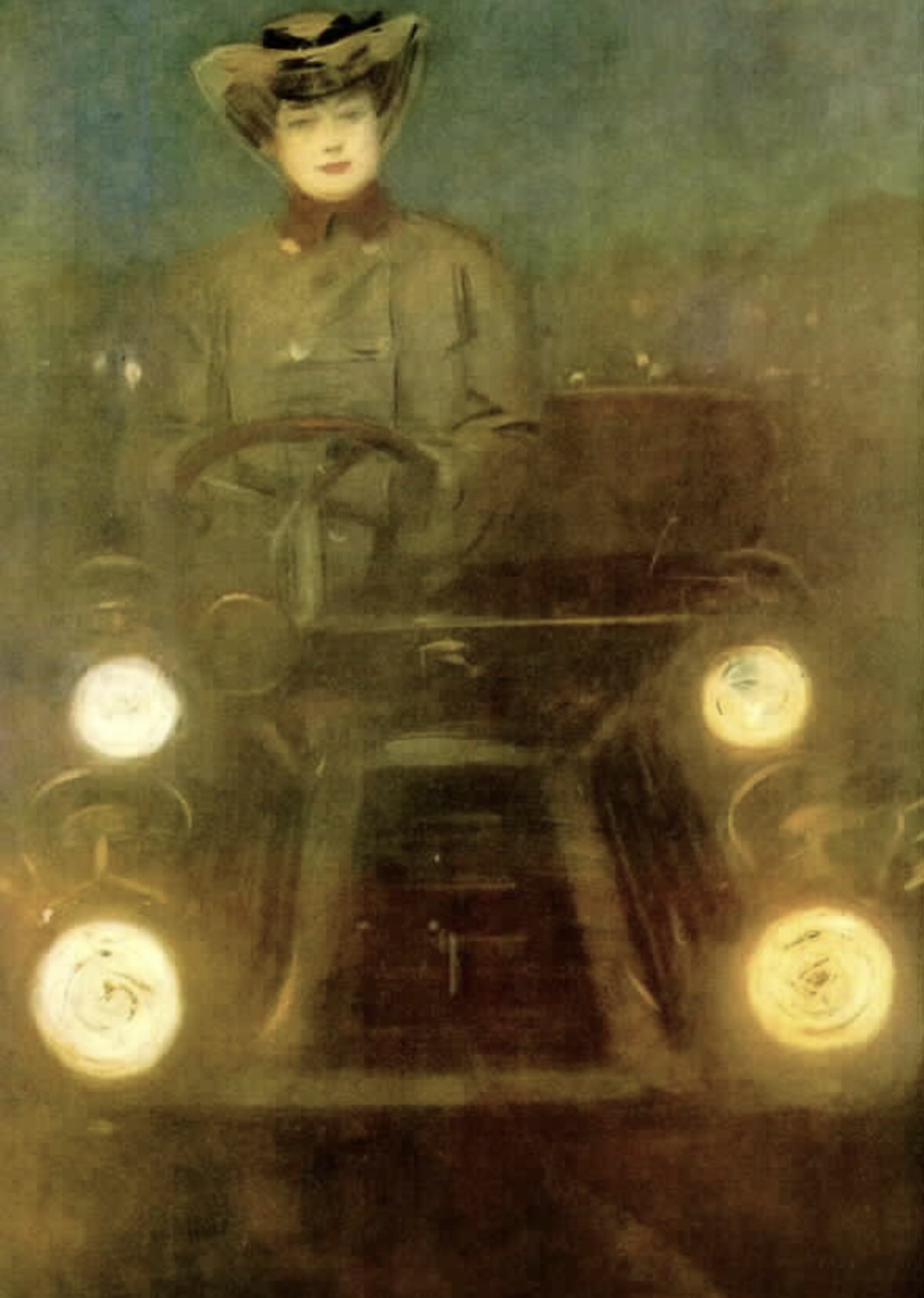

‘La Ruta’ plays out at night in fog beside a busy highway. There’s a glass bus shelter, which is occasionally visited by lonely strangers. There’s a workman in high-vis overalls repairing a junction box. We witness a road accident and a rescue. A seagull crashes against the bus shelter. Another workman comes along to paint some yellow lines. An irate woman falls out of a car with its headlights blazing. ‘F**k you!’ she cries, beating the bonnet with her handbag. She then desperately struggles to remove her trench coat.

La Ruta ©Rahi Rezvani 2022 for Nederlands Dans Theater

The disparate cast stumble and spin, tumble and turn. And all the while they are accompanied by the incessant noise of passing traffic, by blaring horns, flashing lights and long shadows.

This is the stuff of a noir nightmare. And indeed from the outset we encounter curious characters that don’t seem to make much sense. A couple in kimonos; a man running about with a dead bird; a murderous thug throwing boulders. One poor soul has the heart of a roadkill deer transplanted into his chest.

'It’s very difficult to organise a dream, because when you organise it, you wake up. When you take control of a dream, you understand that you are sleeping. This is why, to dream you need to be unprotected.'

Teodor Currentzis

Although we were witnessing a fragmented dystopian dream, the piece for me had a compelling coherence. It conveyed a strong sense of place: how it feels to be out late at night, by the side of a road, in the middle of nowhere. It suggested a desolate, unsettling world of loss and isolation; of violence and peril; of strange events and chance encounters.

‘La Ruta’ is bleak, surreal and curiously moving.

I was struck by the way that this short 35-minute piece managed to mine a great deal from such a simple, ordinary setting. It prompted me to wonder whether, in the communications industry, we spend enough time considering contexts and environments. Do we settle for the commonplace and familiar, the stereotypical and cliched? Or do we create worlds that are vibrant and colourful; intriguing and evocative; rich with symbolism and emotion?

Surely locations can be characters in their own right.

'Come closer and see,

See into the trees.

Find the girl

While you can.

Come closer and see,

See into the dark.

Just follow your eyes,

Just follow your eyes.

I hear her voice,

Calling my name.

The sound is deep

In the dark.

I hear her voice

And start to run,

Into the trees,

Into the trees.’

The Cure, ‘A Forest’ (L Tolhurst / R Smith / S Gallup / M Hartley)

No. 426