Picasso Drinking Gasoline: In Praise of Restless Souls and Inventive Minds

'Study for the Horse Head (I)', a sketch for ‘Guernica’ (1937)

'I begin with an idea and then it becomes something else.'

Pablo Picasso

Picasso sits before his easel in a pair of shorts and no shirt. He is 75. He has been set the challenge of creating an image in 5 minutes with a new felt-tip pen. He sketches with speed and confidence - long fluid lines, bold squiggles, dabs of colour. He stares intently at his canvas. A bunch of flowers becomes a tubby fish, which turns into a jaunty cockerel, and finally a red-eyed faun.

‘I could go on all night if you want.’

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s fascinating 1956 film ‘Le mystère Picasso’ seeks to shed light on Picasso’s creative process. The artist paints on transparent blank newsprint so that the crew can film on the other side. He takes us on a dazzling, restless, inspiring journey.

'Others have seen what is and asked why. I have seen what could be and asked why not.’

The documentary features in the fine ‘Picasso and Paper’ exhibition, currently running at the Royal Academy, London (until 13 April).

Pablo Picasso, Women at Their Toilette, Paris, winter 1937–38

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean

‘By chance I managed to get hold of a stock of splendid Japanese paper. It cost me an arm and a leg! But without it I’d never have done those drawings. The paper seduced me.’

For Picasso paper was a vehicle for expression that was always close at hand. It was a tool for preparatory studies. It was a fertile medium in its own right. He created on writing paper, wrapping paper, wallpaper and newspaper. He sketched on notebooks and napkins, magazines and menus, packaging and postcards. He drew in pencil, oil, ink, crayon and charcoal. He folded and glued, cut and pasted, painted and printed.

'I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.’

The exhibition presents a torrent of ideas, thoughts and feelings, a gushing stream of consciousness. It takes us from two charming silhouettes of a dog and a dove, cut from paper when Picasso was nine years old; through his Blue and Rose Periods; through Cubism, Surrealism and Neoclassicism; all the way to a skull-like self-portrait, in black and white crayon, that he made at the age of 91.

Dog, Málaga, c. 1890 Cut-out paper

© Museu Picasso, Barcelona. Photo, Gasull Fotografia © Succession Picasso/DACS 2020

'To copy others is necessary, but to copy oneself is pathetic.’

On the way we see countless fauns, goats and doves; matadors and minotaurs; harlequins and horses; nudes and portraits; lovers, jesters, cavaliers and circus performers. Picasso burnt two eyes and a mouth into a paper napkin with a cigarette to make a head. He created a plaster cast of a crumpled sheet of paper. He drew a cheeky leg on a Vogue fashion spread.

'Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.’

Picasso clearly had a phenomenal work ethic. He just kept producing fresh, original ideas across all manner of media. He couldn’t help himself.

'Work is a necessity for man. Man invented the alarm clock.’

And he wasn’t afraid of the absurd, the ugly or the obscene. His work is unfiltered, unfettered, uncensored. Freud would have had a field day.

'The chief enemy of creativity is 'good' sense.’

When fellow artist Georges Braques first saw 'Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon' he observed:

'It made me feel as if someone was drinking gasoline and spitting fire.’

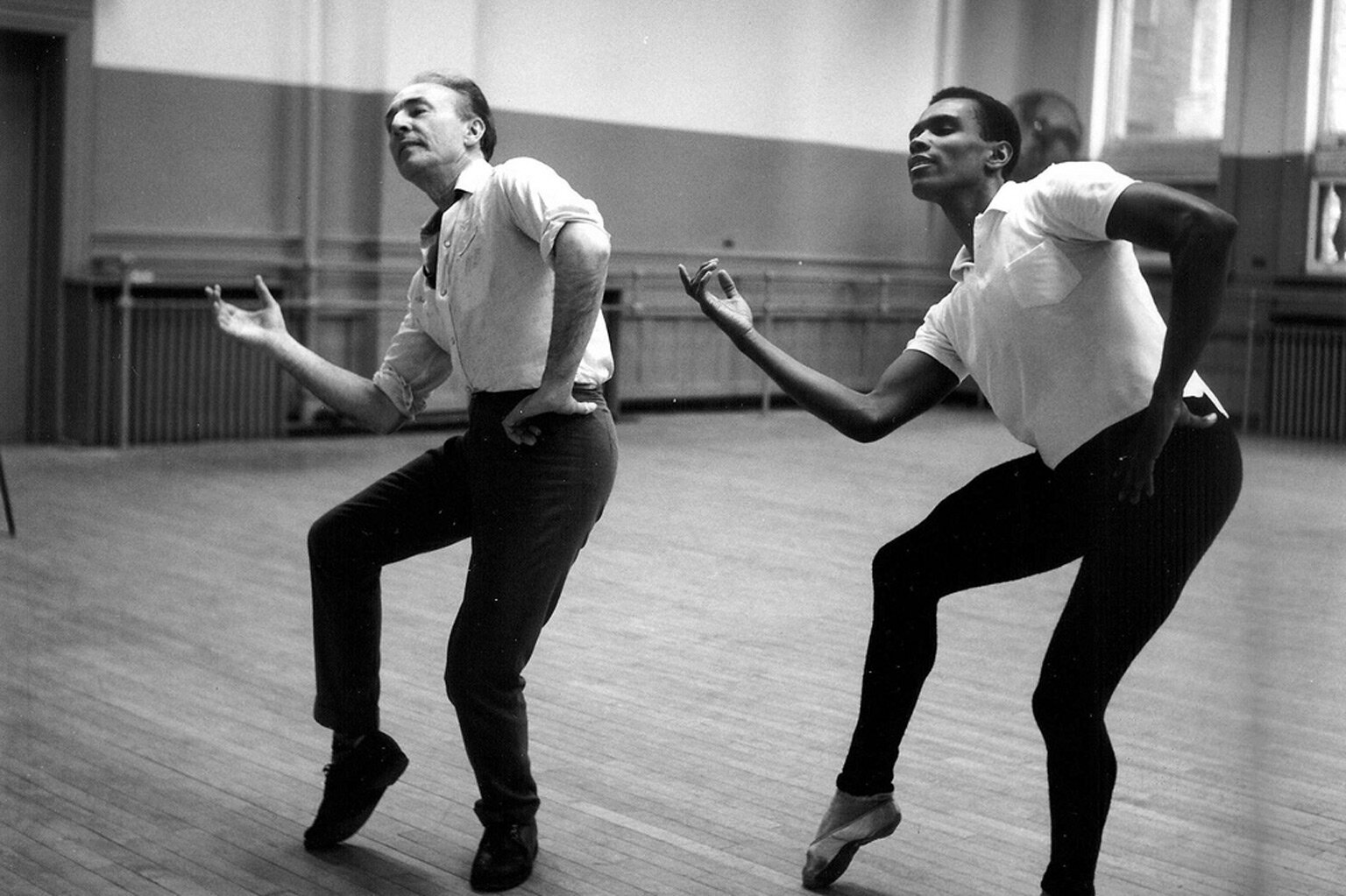

Picasso next to the cut and folded cardboard sculpture of a seated man for Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / image RMN-GP © Succession Picasso/DACS 2020

I left the exhibition in awe of Picasso’s extraordinary appetite for change, his craving to create. He seems to have had a relentless desire to express ideas, to articulate feelings, to explore, to pioneer. He was indeed drinking gasoline.

'If I paint a wild horse, you might not see the horse... but surely you will see the wildness!’

Picasso was, of course, a unique talent and a problematic personality. But he still suggests some simple lessons for people working in the creative professions.

We should cultivate a restless mind - diligent, dynamic, determined; alive to new possibilities and fresh perspectives. We should not seek to check, edit or censor ideas before we’ve given them room to breathe. We should avoid nostalgia; never rest on our laurels; never look back.

'Action is the foundational key to all success.'

Above all, we should reach for a pad. Scribble, sketch, jot and note. Carry a journal, make a list. Devise a scheme, form a theory, hatch a plan, draft an idea, plot an escape.

Go on. Make it up, write it down. Now.

'I do not seek. I find.’

At the end of the Clouzot film Picasso expresses dissatisfaction with one of his images. He sets about over-painting it. ‘But what about the audience?’ Clouzot asks.

‘I’ve never worried about the audience and I’m not about to start now.’

'O, the wayward wind is a restless wind,

Is a restless wind that yearns to wander.

And I was born the next of kin,

The next of kin to the wayward wind.’

Sam Cooke, ‘The Wayward Wind’ (S Lebowsky, H Newman)

No. 269