Brian Friel, the Creative Fool and the Poetry of Place Names

‘And even though they told themselves they were here because of the remote possibility of a cure, they knew in their hearts they had come not to be cured but for confirmation that they were incurable; not in hope but for the elimination of hope; for the removal of that final impossible chance – that’s why they came - to seal their anguish, for the content of a finality.’

Frank, Faith Healer (by Brian Friel)

Brian Friel, the dramatist and short story writer who died last year, was often called ‘the Irish Chekhov.’ In magnificent works like Translations, Aristocrats and Dancing at Lughnasa he wrote of rural communities haunted by history and the scars of colonisation, by lost language and abandoned hope. His plays are nostalgic, funny, humane and intelligent.

I recently saw an excellent production of Friel’s 1979 play Faith Healer at the Donmar Warehouse (running until 20 August). The play considers issues of truth and memory through what was at the time an innovative monologue structure where three characters give three very different accounts of the same events. Faith Healer prompted a number of thoughts about the craft of creativity.

The Creative Fool?

‘Confusion is not an ignoble condition.’

Brian Friel

In Part 3 of Faith Healer, Teddy, the Cockney talent manager takes to the stage. He is a showman and raconteur, perky and perceptive. Having had years of working with creative performers, he offers his own thoughts on the keys to success.

‘Did you ever look back at all the great artists – Old Freddy [Astaire] here, Lillie Langtry, Sir Laurence Olivier, Houdini, Charlie Chaplin, Gracie Fields – and did you ever ask yourself what makes them all top-liners, what have they all got in common? Okay, I’ll tell you. Three things. Number one: they’ve got ambition this size. Okay? Number two they’ve got a talent that is sensational and unique – there’s only one Sir Laurence – right? Number three: not one of them has two brains to rub together.’

Teddy’s judgement is of course harsh and flawed. The great creative talents I have worked with were far from stupid. However, I think there may be something in what he’s saying. Often creative people are more emotionally intelligent than conventionally academic. Orthodox brains deal in history, hard facts and hard data; they like science and certainty. Creative minds on the other hand are more intuitive, instinctive, inquisitive. They are comfortable in uncharted territory, at ease with the unexplained and unresolved.

As the musician Nick Cave said in the excellent 2014 documentary, 20,000 Days on Earth:

‘I’m not interested in that which I fully understand.’

Sometimes I suspect we have a systemic, societal problem on our hands. Institutional and corporate cultures have a way of marginalising open and inquiring minds. They prefer obedience to rebellion, discipline to dreaming. They often denounce the creative spirit as vague, fanciful and naïve. ( It's a theme Sir Ken pursues with great eloquence. ) In another of Friel’s plays, Philadelphia, Here I Come!, he suggests that our schools iron out our emotional selves.

‘They were good times…before we were educated out of our emotions.’

Nonetheless, we should reassure ourselves that emotional intelligence is at least better understood by the general public. Time Out recently reported a remark overheard on the Tube:

‘I’m not stupid. I’m dumb. It’s different.’

The Poetry of Place Names

‘Aberarder, Aberayron,

Llangranog, Llangurig,

Abergorlech, Abergynolwyn,

Llandefeilog, Llanerchymedd,

Aberhosan, Aberporth…’

At the beginning of Faith Healer, Frank, the itinerant faith healer of the title seems to be speaking a foreign language. Is it Gaelic? Is it a mystical chant relating to his profession? We then realise he is incanting a list of Welsh villages that he has visited over the course of his career.

There’s a rhythm and poetry in place names, a romance and resonance about them. Each town name suggests its own unique history and community, myths and untold stories. Places we’ll never visit or never know; lives we’ll never learn about or understand.

Consider how the potency of Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech is enhanced by his repeated reference to particular locations from across the United States, each with its own imagined associations.

‘Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.’

The world of popular song has also long been familiar with the poetry of place names. Early in his career as a songwriter, Jimmy Webb penned a huge hit for Glen Campbell. ‘By the Time I Get To Phoenix’ tugged at the heartstrings as it related the thoughts of a disappointed lover driving through Phoenix, Arizona, across New Mexico to Albuquerque and then onto Oklahoma. It's a song that paints pictures as it progresses.

Campbell seemed alert to the fact that in part the lyric’s resonance derived from its locations. He called Webb to ask for more of the same.

‘Can you write me a song about a town?’

When the songwriter hesitated, Campbell pressed him.

‘Well. Just something geographical.’

Webb went on to write the glorious Wichita Lineman.

Inevitably one has to ask whether we in the world of marketing and communications properly capitalise on this theme. Actually, I think over the years a good deal of compelling creative work has demonstrated the poetry of place names.

In my youth kids were told that if they didn’t drink milk, they’d only be good enough to play for Accrington Stanley. Many will recall how the snack brand Phileas Fogg made light of its prosaic origins in Medomsley Road, Consett. More recently our food, supermarket and restaurant brands have suggested that specificity of origin justifies premium.

And then, of course, there’s my favourite: the ‘70s ad for Campari, featuring the proudly proletarian Lorraine Chase.

‘Were you truly wafted here from paradise?’

‘Nah, Luton Airport.’

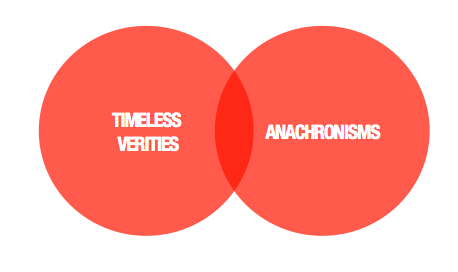

Finding the Universal in the Particular

‘In the particular is contained the universal.’

James Joyce

Perhaps there is a broader lesson we should learn here. James Joyce said that he wrote about Dublin because it was the world he knew best and because he believed that universal truths were revealed in the particular.

Given that in marketing we seek to express unifying truths, do we subscribe to Joyce’s wisdom?

I’m inclined to say that nowadays we too often leap directly to the universal, skipping the particular along the way. We are nervous of specificity, naturally inclined towards archetypes and stereotypes. We are predisposed to grand sweeping statements and generalisations. And this is especially the case with bigger brands, operating across wider geographies, with broader concepts.

Maybe we should just occasionally think small to act big.

No. 93