Is Beauty Good?

Is there a moral responsibility to make products, experiences and communications beautiful?

Earlier this year I attended an exhibition of Ancient Greek sculpture at The British Museum. (Defining Beauty)

Graceful young men with muscled torsos and tousled locks; pensive women with tastefully coiffed hair, gossamer veils and elusive smiles. The sculptures were at once naturalistic and idealised. Elegant exercises in posture and poise, expertly carved from creamy white marble. It was an inspiring show.

The Ancient Greeks were the original humanists. They subscribed to the philosopher Protagoras’ view that ‘man is the measure of all things,’ and they attached a particular value to the human body. Their gods readily adopted human form. And whilst other cultures had associated nakedness with vulnerability, the Greeks considered nudity to be heroic. They practised nude in their gymnasia and competed nude at their games.

The Greeks also theorised about beauty. Aristotle wrote that ‘the chief forms of beauty are order, symmetry and clear delineation.’ Polykleitos’ Spear Bearer was designed according to mathematically determined ratios of the perfect human body. Myron’s Discus Thrower was an exercise in order and balance. One arm grips the discus, the other hangs loose; one leg bears the body’s weight, the other is relaxed.

Given this fascination with physical form, it is perhaps no surprise that the Greeks often spoke of the virtuous man being ‘beautiful and good’ (‘kalos k’ agathos’). For the Greeks there was an ethical dimension to beauty.

One can’t help thinking that our own culture’s obsession with the body beautiful began here. We attach an incredible importance to beautiful people, to how they live and what they say. We’re obsessed with appearance and attitude, self-image and selfies, pouts and poses, diets and disorders. We want to walk like a supermodel; talk like a film star; look like an It Girl. It sometimes seems so out of control. Like the Greeks, we assume that beautiful people are better people.

We should, of course, beware Greeks dispensing wisdom. They were wrong to associate physical attractiveness with moral superiority. They were wrong to suppose that they could be arbiters of beauty, or that it could be reduced to a mathematical calculation. But I wonder were they also half right? Is there nonetheless an ethical dimension to beauty?

Many years ago my old Ad Agency boss, the maverick Planning genius John Madell, told me that, if we intrude upon people’s lives, we have a responsibility not to pollute those lives with the asinine and the ugly.

I’m sure he was right. I well recall there was a vogue in mid ‘90s brand communication for the rough and ready, the low-fi and the under-produced. I hated that period. Amateurism celebrated in the name of authenticity and ‘keeping it real.’

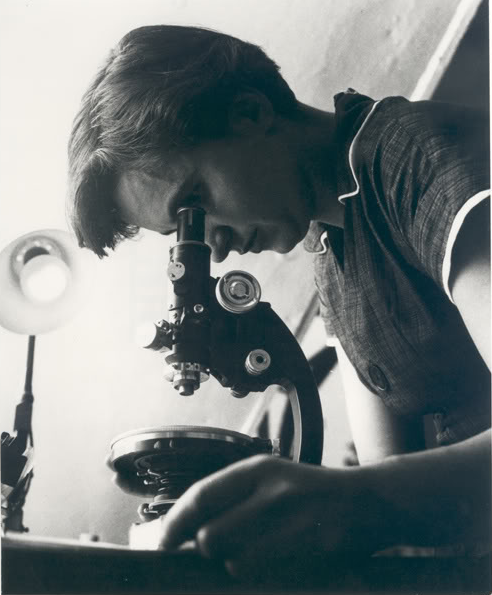

Art direction matters. So does quality in type and design, casting and wardrobe, illustration, photography and film. So does craft in music and sound engineering, reproduction, retail space and product design. So does expertise in editing, identity and user experience, consumer interface and the customer journey. These elements create the architecture of brand aesthetics. And I believe good brand aesthetics are a moral imperative in the modern age.

Advertising and marketing occupy so much space, time and attention in people’s lives. Shouldn’t brands acknowledge that there is an ethical responsibility: to make the world a little more interesting, a little more thoughtful, a little more beautiful?

For some time now brand leaders have recognised that we have a social responsibility to leave the world better than we found it. Is there not also a social responsibility to leave the world more beautiful than we found it?

Because beauty is good.

No. 53