(Don’t) Turn Your Back On Me

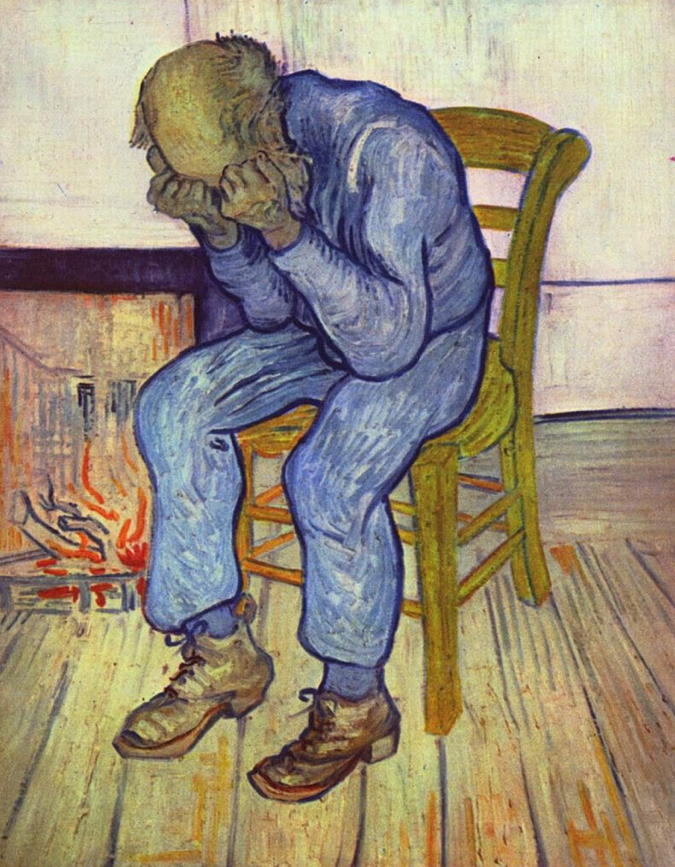

I attended an Edvard Munch show at the Tate Modern. Dark, melancholy, awkward stuff. Angst, loneliness, jealousy. A difficult relationship with society in general and women in particular.

It was striking that he painted quite a lot of pictures of women with their backs to the viewer. A powerful expression of exclusion, loneliness, unrequited love.

I spent my youth being turned away from London’s elite nightspots. Perhaps it was the sleeveless plaid shirt, the white towelling socks, the caked on Country Born hair gel. But the bitter sense of disappointment hasn’t left me. I can taste it now. And I learned more about clubbing from Spandau Ballet videos than actual experience…

‘He was despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.’

Handel, Messiah

As a young executive I was invited to apply for an Amex card. I applied and was duly rejected. Naturally I was confused and disappointed and I never spoke to them again. I’m sure consumers often feel a similar sense of exclusion from brands. Refusal and denial are shaming, embarrassing. The fear of rejection is almost as powerful as rejection itself. And then there are the coded gestures, the arcane language, the gender and cultural specific semiotics. The feeling that you don’t belong, that you’re not welcome here. It’s a private conversation, you wouldn’t understand.

I guess that’s why strategists so often recommend that brands are more open, inviting, transparent. We want brands to look us in the eye, to reach out from the canvas with a knowing glance and a welcoming smile. Easier said than done, of course.

Yet the turned back does not have to be all bad.

The Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershoi often painted a solitary woman with her back to the viewer. She goes about her daily routine in a quiet middle class home, lost in private thought. Hammershoi’s subjects seem more loved than feared. This distinctive reverse view gains its power in part from being so unusual. But also from the sense of intrusion on private time. The sense of seeing, but not being seen. It’s a little awkward, but also intriguing. Am I encountering her truest self, her identity freed of relationships, social constraints and concerns about appearance?

It reminds me of the oft’ cited quote from George Bernard Shaw: ‘Ethics is what you do when no one is looking.’ (I’ve uncovered versions of this quote from many sources. Henry Ford said ‘quality means doing it right when no one’s looking’. And of course, most recently Bob Diamond suggested ‘culture is how we behave when no one’s watching.’)

So how do brands behave when no one is looking? What would the brand encountered in a quiet room be up to? Would we find it dutifully engaged in customer-centric endeavours? Would its jaunty personality be sustained when there’s no one to impress? Would we discover an honest engagement with issues of citizenship and responsibility?

I’m worried that we’d most likely find the brand plotting a marketing and PR plan. I’m worried that in business as in politics too much thought nowadays is given to how things will play, how they will be perceived and reported. I suspect that too often the brand’s instinctive ethical and commercial compass has been replaced by recourse to brand image tracking and favourability ratings.

I appreciate this may be a curious thing for an adman to say. I should perhaps celebrate the triumph of modern marketing, the inevitable victory of perception in the All Seeing Age. Perhaps like a modern celebrity the smile must always be on, the guard must always be up. But it still makes me a little melancholy…

And what of Agencies? How do we behave when no one’s looking?

We are often perceived as conventions of feckless youth and superannuated yuppies. And I confess I was a little uncomfortable when Clients first started plugging in laptops, decanting lattes and working at our offices. I worried that they’d disapprove of our timekeeping, that they’d be offended by our cussing.

But as more Clients have made the Agency their mid-week home, I think the Agency has benefitted. The Embedded Client often sees passion, industry, talent and integrity. They get to see our truest self. And it’s not as bad as they, or we, may have expected.

In the words of the great Brit Soul luminary, David Grant…‘I’ve been watching you watching me. I’ve been liking you, Baby, liking me…’

First published BBH Labs: 10/09/

No. 15