Exquisite Corpse: If You Want To Change the Product, Try Changing the Process

'Nude Cadavre Exquis' Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Max Morise, Man Ray (1926-27)

‘There’s a method to my madness; and a madness to my method.’

Salvador Dali

At a gallery recently I came across an Exquisite Corpse.

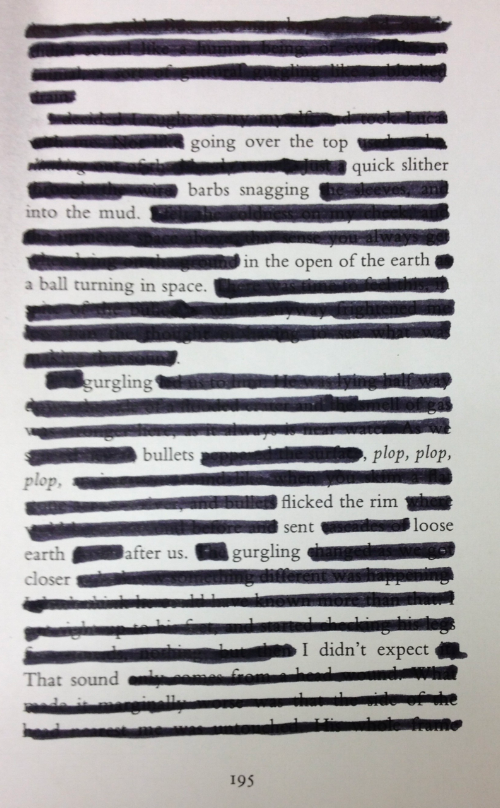

Exquisite Corpse was a creative technique that Surrealist artists adapted from the traditional parlour game of Consequences. Typically four people took turns to draw a different bodypart on a folded piece of paper: first the head, then the torso, then the hips and finally the legs. Each participant was unaware of what the previous contributors had drawn. The image that resulted was often comic, disturbing, absurd.

Exquisite Corpse at first struck me as a curiously playful distraction for serious artists. Just a bit of fun perhaps before they got back to proper work. But the Surrealists were serious about the technique. For them it illuminated the creative process: it was a way of exploring the impact on their art of multiple authorship, sequencing, chance and the unconscious.

For Surrealists process didn’t have to be a constraint on creativity; it could be a catalyst to it.

'La Clairvoyance'Rene Magritte

‘All my life my heart has yearned for a thing I cannot name.’

Andre Breton

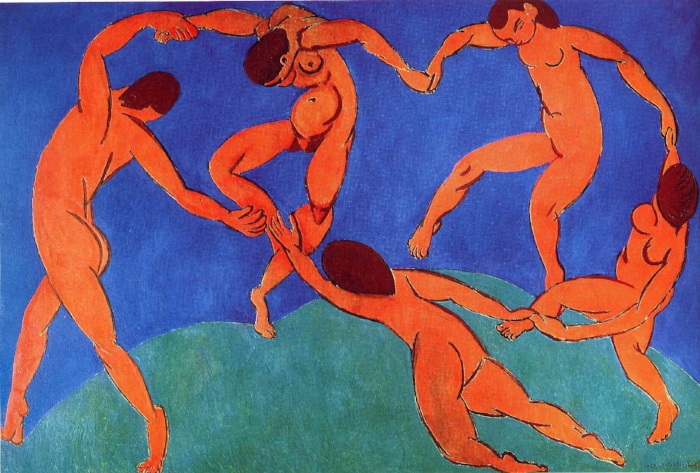

The writers and artists of the Surrealist movement gathered in Paris in the 1920s around their leader, Andre Breton. In the wake of the horrors of the First World War, they determined to suppress reason, reality and ‘bourgeois aestheticism.’ Like Freud they were interested in dreams and the workings of the unconscious mind; in juxtapositions and coincidences; in everyday strangeness.

In particular the Surrealists experimented with the process of creation, disrupting traditional practice at every opportunity. They adopted techniques like ‘automatism’: writing and drawing at random without rational or conscious control. They set up the Bureau of Surrealist Research to record the dreams of the general public. They created collages that integrated found material, text from popular novels, images from magazines and encyclopaedia. They untethered objects from their names and practical functions. They experimented with photography as an art form.

For the Surrealists new techniques provided a springboard to new acts of creation. Process inspired product.

‘I’ve never been able to finish a detective story because I don’t give a hang who was the murderer… It doesn’t interest me at all. It’s the mental processes that interest me.’

Man Ray

'Object' Meret Oppenheim

In the world of commercial creativity we tend to regard process with ambivalence. It’s boring but important; a necessary evil. We often characterise it as something to be avoided or reduced as far as possible; as an enemy of creativity.

Working at BBH for many years, I was quite taken with its distinctive belief in ‘processes that liberate creativity.’ This seemed a more mature position. I learned that process protects time, prevents misunderstanding and wasted effort. It generates alignment within a team, harnesses creativity to a commercial agenda and optimises the chances of great outcomes. I learned to be respectful of roles and responsibilities, of sign-offs and the sequencing of actions. I learned that process can be the creatives’ friend.

But the idea of ‘processes that liberate creativity’ goes beyond commercial efficiency. As the Surrealists suggested, new processes can inspire new ideas. They can be a fuel for the imagination. They can provoke change.

So processes should not be engraved in granite. They should be constantly questioned and evaluated, rewritten and reformulated.

How can we accelerate and stimulate innovation? Why not change the brief, change the team, change the time, change the meeting? Let’s investigate new combinations and partnerships. Let’s crash the procedure and crunch the schedule. Let’s test and trial, experiment and explore.

At times of transformation we should all be looking to disrupt incumbent ways of doing things; to invent new models, modes and techniques. Not just so that we can cut costs or increase speed; but so that we can create fresh routes to original ideas; novel sources of imaginative thought.

If you want to change the product, try changing the process.

‘Freedom is not given to you – you have to take it.’

Meret Oppenheim

No. 131