Lumet’s Lessons: Preparing for Lucky Accidents

‘All great work is preparing yourself for the accident to happen.’

Sidney Lumet

Between 1957 and 2007 Sidney Lumet directed some 50 films. He gave us thrilling legal dramas, like ’12 Angry Men’ and ‘The Verdict’; gripping analyses of corrupt institutions, like ‘Serpico’ and ‘Network’; and searing psychological stories, like ‘The Pawnbroker’ and ‘Dog Day Afternoon’. He presented us with moral ambiguity, isolated anti-heroes and prisoners of conscience; flawed individuals struggling to find justice and truth. He was known as ‘the Dickens of New York’, ‘the actor’s director.’ And he taught us a great deal about the creative craft.

‘If you prayed to inhabit a character, Sidney was the priest who listened to your prayers, helped them come true.'

Al Pacino

1. Start with Empathy

‘All good work is self revelation.’

Lumet was born in Philadelphia in 1924 to Polish immigrant parents who worked in the Yiddish theatre. He grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, studied acting at the Professional Children's School, and, from the age of 5, appeared in several Broadway productions and one movie. After attending Columbia University, he served as a radar repairman in India and Burma during World War II. On his return he enlisted as a member of the inaugural class at New York's Actors Studio.

Lumet loved drama, but he realised that performing was not for him. So he set up his own theatre workshop and appointed himself director, while also teaching at the High School of Performing Arts.

His early experience gave him a life-long empathy with actors.

‘I understand what they're going through. The self-exposure, which is at the heart of all their work, is done using their own body. It's their sexuality, their strength or weakness, their fear. And that's extremely painful.’

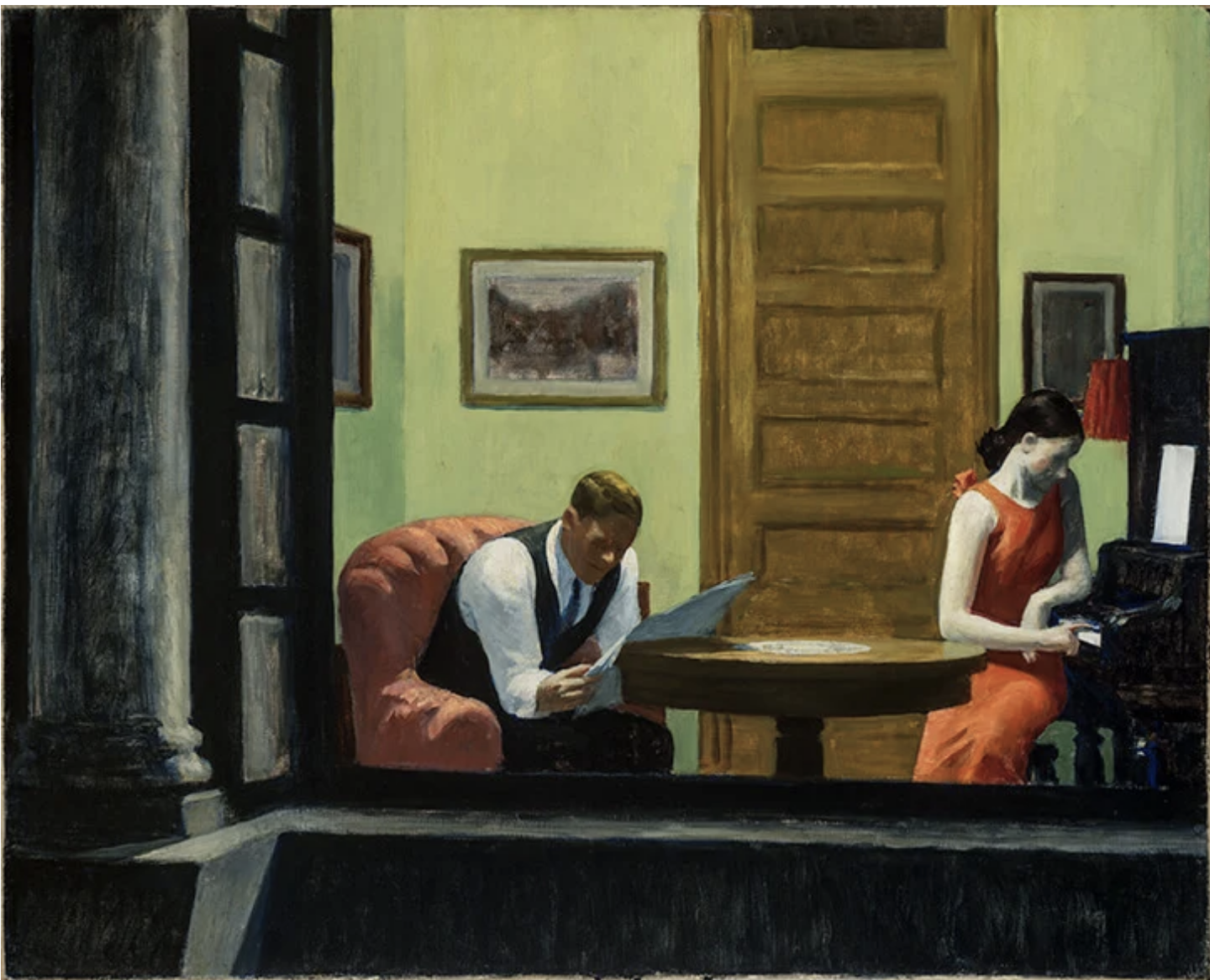

Scene from 12 Angry Men

2. Turn Your Disadvantages into Advantages

In 1950 Yul Brynner, who was directing television dramas at the time, invited Lumet to join him at CBS. When Brynner left to star in ‘The King and I,’ Lumet took over. He shot two live shows a week: murder mysteries, comedies and original plays. His output included the innovative ‘You Are There’, a series that covered historical events – such as the death of Socrates and the Boston Tea Party - with modern news techniques.

In 1957 Lumet was commissioned to produce his first movie, ‘12 Angry Men’ starring Henry Fonda. A taut examination of the US jury system - shot in just 19 days - the drama played out in a claustrophobic jury room one sweltering New York summer.

From the outset Lumet displayed a thoughtful and imaginative approach to his craft.

‘It never occurred to me that that was a difficult thing to do, to do a whole movie in one room. You come in with a certain arrogance when you’re young… I knew that the way to do it was to turn what was seemingly a disadvantage into an advantage. As the movie went on, I made the room smaller: the lenses got longer and longer, so that walls kept pulling in closer and closer, the camera kept dropping, dropping, dropping, so finally the ceiling was right over their heads. So that actually the whole piece kept contracting. And dramatically that’s what the movie was about.’

3. Be Whatever They Need You to Be

In the early phase of his film career Lumet was often tasked with translating stage plays onto the big screen. Between 1960 and 1962 he adapted classics by Tennessee Williams, Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller.

Lumet’s theatre background clearly impacted his style of movie direction. He rehearsed a minimum of two weeks before filming, and during that time he also blocked the scenes with his cameraman. Consequently, when it came to the actual production, he would usually shoot a scene in one take, two at the most, and he consistently delivered on time and on budget.

Lumet had a natural affinity with actors. He worked with them individually on their parts and he was happy to share ideas. He would often improvise dialogue and had the best exchanges incorporated in the script.

‘My job is to be whatever they need me to be. I’m no believer in any particular kind of technique. I’ll work any way they want to work.’

Image from The Hill

4. Trust Your Instinctive First Response

Lumet soon broadened his output beyond stage adaptations. His work tackled serious, psychological themes: the agonies of conscience; guilt and innocence; honesty and truth.

‘The Pawnbroker’ (1964), starring Rod Steiger, reflected on the enduring mental scars of a Holocaust survivor living in Harlem. ‘The Hill’ (1965), with Sean Connery, examined the brutality of a military prison. ‘Fail Safe’ (1964), again featuring Henry Fonda, exposed the ease with which Cold War misunderstandings could escalate into nuclear destruction.

In selecting a script Lumet always trusted his gut.

‘I respond to a script or an idea completely instinctively, don’t try to analyse it, don’t try to fit it into a preconceived notion of what I want. And then, after a number of years, I can look back and I can say: ’Oh, that’s what I was interested in at that time.’’

5. Plunge in with Faith

Lumet extended this instinctive approach into the production process.

‘Self deception is really necessary to even go to work in the first place. Because the work itself is so hard you’ve got to be prepared to say: ‘I believe in this. I don’t see the problem.’ A kind of plunging in with faith.’

Lumet continued to be fascinated by the technical possibilities available to him in film. In ‘The Pawnbroker’ he used flashbacks to communicate the persistence of memory. In ‘The Hill’ he employed just three lenses: 24, 21 and 18mm. As the drama developed, he distorted the foreground and let the background recede to create the impression of escalating mental pressure.

Lumet compared his process to that of making a mosaic.

'Someone once asked me what making a movie was like. I said it was like making a mosaic. Each setup is like a tiny tile. You color it, shape it, polish it as best you can. You'll do six or seven hundred of these, maybe a thousand. Then you literally paste them together and hope it's what you set out to do. But if you expect the final mosaic to look like anything, you’d better know what you’re going for as you work on each tiny tile.’

Sidney Lumet with Al Pacino on the set of Serpico. Photograph: Everett Collection/Rex Features © Artists Entertainment Complex

6. Set the Mental Juices Flowing

Having grown up in New York during the Depression, Lumet witnessed a good deal of poverty and corruption. His films often focused on malpractice in the system and the fragility of justice.

‘If we are to have faith in justice we need only to believe in ourselves and act with justice. I believe there is justice in our hearts.’

‘Serpico’ (1973) starring Al Pacino, told the story of a whistleblower in the New York City police force, ‘a rebel with a cause.’ ‘Network’ (1976) presented Peter Finch as a news anchor suffering a breakdown, railing against the iniquities of modern media. ‘The Verdict’ (1982) featured Paul Newman as a washed up lawyer taking on a medical negligence case to salvage his career.

'I have always been fascinated by the human cost involved in following passions and commitments, and the cost those passions and commitments inflict on others.'

Lumet consistently aimed for more than entertainment.

‘While the goal of all movies is to entertain, the kind of film in which I believe goes one step further. It compels the spectator to examine one facet or another of his own conscience. It stimulates thought and sets the mental juices flowing.’

7. If It Moves You, It’ll Move Them

For the most part Lumet was a social realist. He insisted on the most natural light and he edited his films so the camera was unobtrusive. He employed camera techniques sparingly and only in service to the core theme of the movie.

‘I hate technique for the sake of technique.’

Conscious that the urban environment provided a vibrant canvas for his work, and sensitive to the particular rhythms of his hometown, Lumet preferred to shoot in New York.

‘Locations are characters in my movies. The city is capable of portraying a mood a scene requires…. New York is filled with reality; Hollywood is a fantasyland.'

Lumet often worked with true stories. 1975’s ‘Dog Day Afternoon’, based on real events that took place in Brooklyn three years earlier, starred Al Pacino as a small time crook who plans a robbery to pay for his partner's sex reassignment surgery. But the heist goes badly wrong and turns into a hostage situation under the media spotlight.

The film included an emotionally draining scene in which Pacino’s character calls home. Lumet incurred Pacino’s anger by asking him to do a second take. But the director had a reason.

‘When we’re tired we weep more easily, we laugh more easily. We’re just wide open.’

Lumet didn’t double guess the public’s reactions. His driving principle was that if a shot moved him, it would move them.

‘If I'm moved by a scene, a situation... I have to assume that that's going to work for an audience.’

8. Prepare for Lucky Accidents

Lumet had a strong work ethic, developing more than one movie a year for most of his career.

‘If I don't have a script I adore, I do one I like. If I don't have one I like, I do one that has an actor I like or that presents some technical challenge.’

Inevitably this prolific approach led to as many failures as successes.

I’m just a great believer in quantity – more chances for the accident to happen…I need one hit, so I can get the money for three more flops.’

Lumet believed that there was a price to pay for ambitious film-making.

‘Great scripts can be screwed up more easily. Because the demand that they make is so much greater. Is there anything more boring than a bad Hamlet?’

Lumet saw his role as maximising the chances of ‘lucky accidents.’

'The truth is that nobody knows what this magic combination is that produces a first-rate of work. I’m not being modest. There’s a reason some directors can make first-rate movies and others never will. But all we can do is prepare the groundwork that allows for the ‘lucky accidents’ that make a first-rate movie happen. Whether or not it will happen is something we never know. There are too many intangibles.'

1976 Sidney Lumet & Faye Dunaway on the set of 'Network'

9. Make Sure Everyone’s Going in the Same Direction

In the course of his career Lumet was nominated four times for a directing Oscar. But he never won. He lost out to some great movies: 'The Bridge on the River Kwai’, 'One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest' and ‘Gandhi.’ In 1976 the Academy preferred ‘Rocky’ to Lumet’s masterpiece ‘Network.’

‘Everyone was saying we were going to take it all. And on the flight out to LA, [screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky] said, 'Rocky's going to take Best Picture.' And I said, 'No, no, it's a dopey little movie.' And he said, 'It's just the sort of sentimental crap they love out there.' And he was right.’

In 2005 Lumet was presented with an Honorary Academy Award.

‘I wanted one, damn it, and I felt I deserved one.’

Lumet died at the age of 86 in 2011.

In some ways, with his gritty depictions of the modern city and his concern for individual conscience and social justice, Lumet was a director in the neo-realist tradition. But in his empathetic relationship with his actors and his instinctive judgement, he also looked forward. And he provided us with a compelling definition of contemporary leadership in any field.

‘My job is to get the best out of everybody working on [the film]. And make sure we are literally going in the same direction. That’s why I’m called the Director.’

'Accidents will happen,

They only hit and run.

You used to be a victim, now you're not the only one.

Accidents will happen,

They only hit and run.

I don't want to hear it, because I know what I've done.’

Elvis Costello and the Attractions, ‘Accidents Will Happen'

No. 436