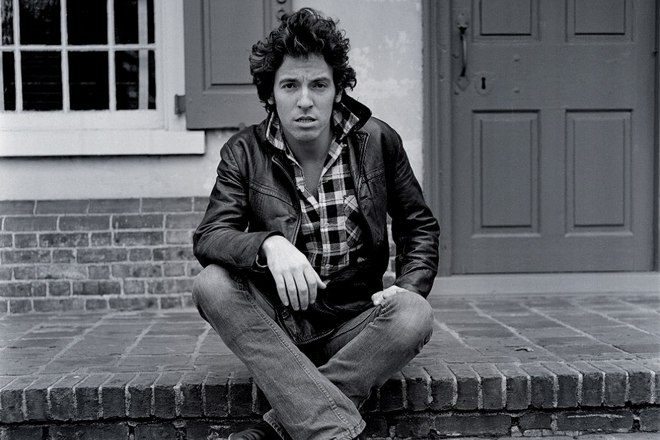

‘I Made It All Up’: Bruce Springsteen and the Art of Invention

‘We are ghosts or we are ancestors in our children's lives. We either lay our mistakes, our burdens upon them, and we haunt them, or we assist them in laying those old burdens down and we free them from the chain of our own flawed behavior.'

Bruce Springsteen, ‘Springsteen on Broadway’

I recently watched ‘Springsteen on Broadway’ (Netflix), the film record of Bruce Springsteen’s 2017-18 residency at the Walter Kerr Theatre, New York.

I’ve always been an admirer of Springsteen. As a youngster I fell for the romantic picture he painted of blue collar America. He sang about his family and friends, home and hometown; about cars and girls, escape and the open road; about dancing in the dark and racing in the streets; about broken promises, burnt out Chevrolets and the land of hope and dreams. He was a sentimental storyteller, a soulful troubadour. He was the future of rock’n’roll.

‘Springsteen on Broadway’ is not a conventional gig. The singer weaves stripped down versions of some of his more famous numbers around a spoken narrative about his life and career. For the most part he stands alone on stage, in dark jeans and t-shirt. Lean and tanned, face chiseled, eyes beaming, a smile never far from his lips, he commands our attention.

He explains what his hometown, Freehold, New Jersey, meant to him when he was growing up.

‘There was a place here. You could hear it, you could smell it. A place where people made lives, and where they worked and where they danced, and where they enjoyed small pleasures and played baseball, and suffered pain; where they had their hearts broken and where they made love, had kids; where they died and drank themselves drunk on spring nights; and where they did their very best, the best they could to hold off the demons outside and inside that sought to destroy them and their homes and their families and their town.'

Springsteen speaks with a preacher’s zeal, testifying to the ties that bind. He prompts us to recall why we loved the United States in the first place; reaffirms the fundamental dignity of the working class; reminds us that masculinity doesn’t have to be toxic; restores our faith in the transformative power of rock’n’roll music.

‘The joyful, life-affirming, hip-shaking, ass-quaking, guitar-playing, mind and heart-changing, race-challenging, soul-lifting bliss of a freer existence… All you had to do to get a taste of it was to risk being your true self.’

Springsteen’s emotive themes resonate particularly in a contemporary setting, when there’s so much doubt about America and its place in the world – when there’s a darkness on the edge of town.

‘These days some reminding of who we are and who we can be isn’t such a bad thing.’

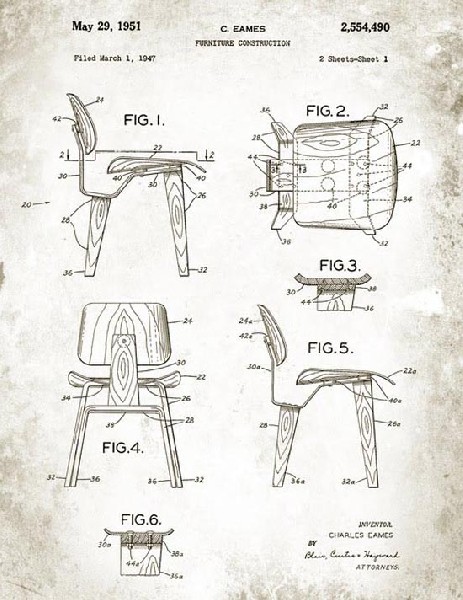

There’s a compelling moment early in the show when Springsteen comes clean about the source of his classic blue collar narratives.

'I come from a boardwalk town where everything is tinged with just a bit of fraud. So am I … I’ve never held an honest job in my entire life. I've never done any hard labor. I've never worked nine to five… I’ve never seen the inside of a factory and yet it’s all I’ve ever written about. Standing before you is a man who has become wildly and absurdly successful writing about something of which he has had absolutely no personal experience. I made it all up.'

Though Springsteen had little first hand experience of working class struggle, it becomes clear, nonetheless, that his storytelling gift was rooted in observation of the community he grew up in, awareness of its strengths and passions, sensitivity to its trials and tribulations. Moreover, many of his songs were inspired by his father - ‘my hero and my greatest foe’ - a complex man of Dutch Irish descent, who was haunted by depression and drink and struggled to find work.

‘Now those whose love we wanted but didn’t get, we emulate them. It’s the only way we have in our power to get the closeness and the love that we needed and desired.’

It is conventional to characterize composers and storytellers as lonely, isolated souls, as outsiders struggling to articulate their unique personal vision and experience. Springsteen’s narrative, by contrast, expresses an intense sense of belonging - to family, community and country – harnessed to acute observational skills. He has profound empathy and emotional intelligence. He feels for other people. And this equips him to tell their stories.

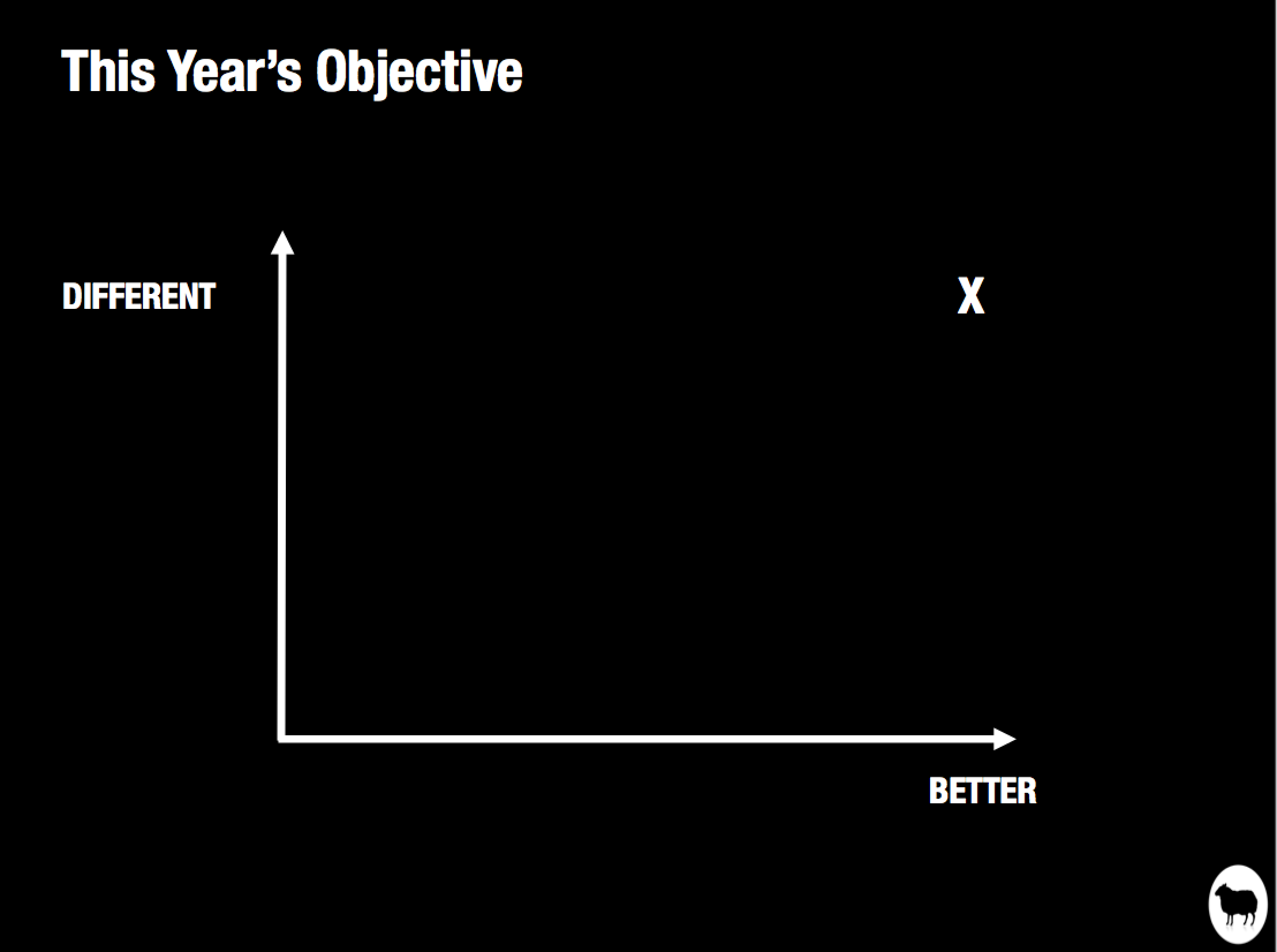

Springsteen should prompt all of us working in creative industries to interrogate our own roots, background and community: How have my history and culture made me? How have I been influenced by my parents and siblings? How am I a product of my hometown?

When confronted by a taxing brief or a blank sheet of paper, when struggling for a creative spark, the inspiration may be close to home.

'I met her on the strip three years ago

In a Camaro with this dude from LA.

I blew that Camaro off my back and drove that little girl away.

But now there's wrinkles around my baby's eyes

And she cries herself to sleep at night.

When I come home the house is dark,

She sighs "Baby did you make it all right."

Tonight, tonight the highway's bright,

Out of our way mister you best keep.

'Cause summer's here and the time is right

For racing in the street.'

Bruce Springsteen,’Racing in the Streets’

No. 215