Good Night, Oscar: Where Is the Line and When Do You Cross It?

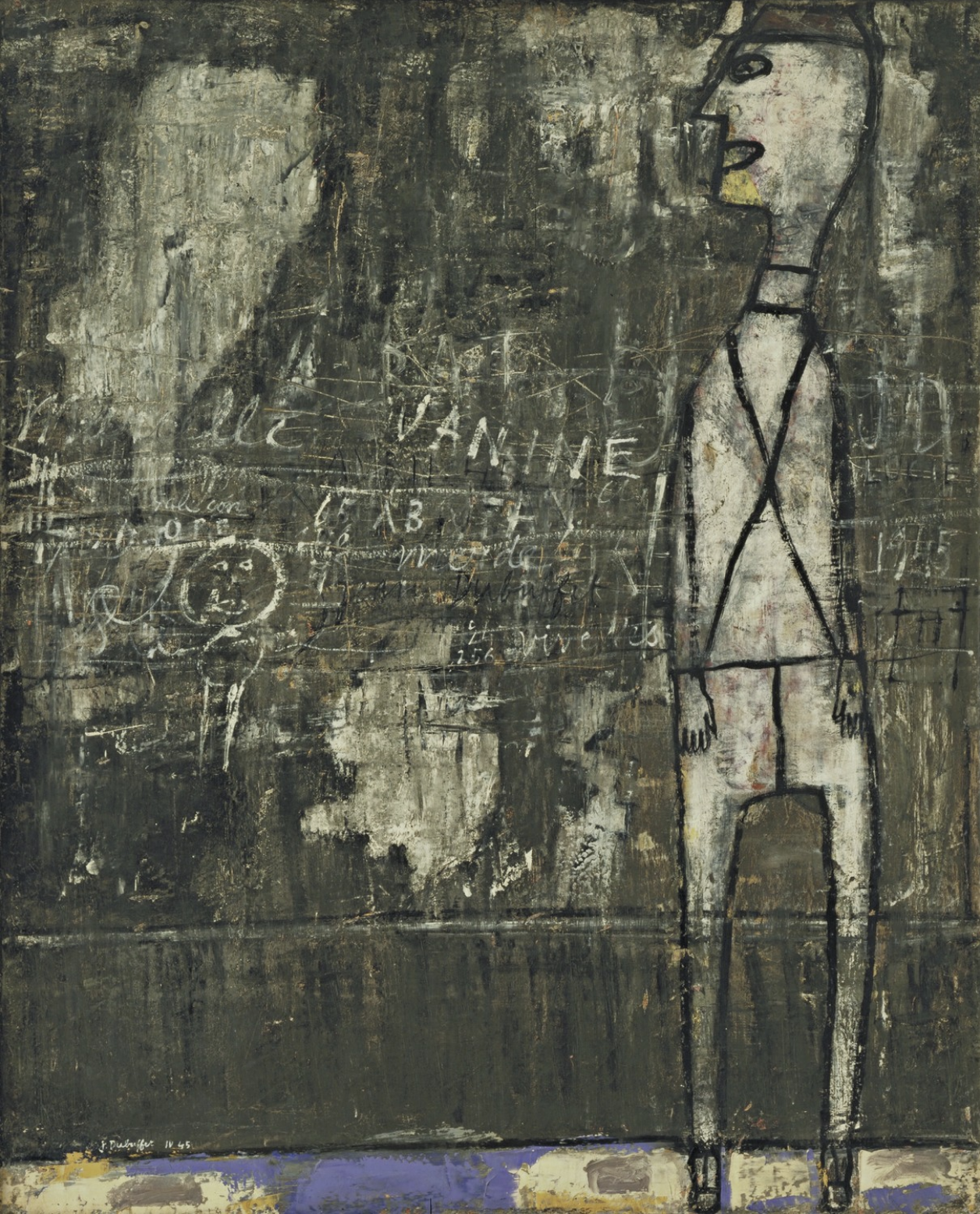

Sean Hayes and Rosalie Craig as Oscar and June Levant in 'Good Night, Oscar'

‘It’s not what you are; it’s what you don’t become that hurts.’

Oscar Levant

Doug Wright’s splendid play ‘Good Night, Oscar’ (The Barbican Theatre, London until 21 September) considers (in Wright’s words) ‘the thin line between entertainment and exploitation; the cost of entertainment to the individual; censorship and what constitutes acceptable humour in our increasingly tender age.’

Oscar: What the world needs is more geniuses with humility. There are so few of us left.

It’s 1958 and Jack Paar, the smooth-talking host of NBC’s The Tonight Show, is asked by studio executive Bob Sarnoff to defend his decision to invite Oscar Levant as a guest. Levant is an accomplished pianist, composer and raconteur. But he is also unreliable, irascible and outspoken.

Jack: Folks are in bed, watching the TV screen through their feet, and Oscar jolts them awake. They know he’s a goddamn lion, and all I’ve got is a whip and a cane-back chair. And for that they’re willing to pay five hundred bucks for a twenty-one inch Zenith, and go to work groggy every morning. All in the hope that they’ll catch him saying something on television they know damn well that you can’t say on television. That’s the moment no one wants to miss.

When we meet Levant, we discover a morose man, with poor posture and shabby clothes. A superstitious hypochondriac, prone to mood swings and addicted to pills, he suffers obsessive compulsive disorder, and has a ritualised way of smoking a cigarette and preparing coffee. He is always in search of ‘a new audience for old stories.’

Oscar: Underneath this flabby exterior, there’s an enormous lack of character.

We also learn that Levant has recently been committed by his wife June to the Mount Sinai mental health facility, and that he’s only been released today on a four-hour pass.

Oscar: She’s a cunning woman, my wife. She drove me crazy, then had me committed. Talk about your perfect crimes…

Jack Paar hosting The Tonght Show

When a sceptical Sarnoff asks Levant to sketch out the interview in advance of the show, Levant is incensed.

Oscar: You’re gonna kill the one thing you’ve got going for you? Spontaneity?

Sarnoff explains that some themes are out of bounds.

Bob: There are just a few topics we’d like you to avoid – the same ones you’d avoid at, say, a dinner party.`

Oscar: I don’t go to dinner parties…I don’t like it when people watch me eat.

Sarnoff perseveres, and contends that a chat show should not take viewers by surprise, shock them, or make them uncomfortable.

Oscar: You know what people do when they’re surprised, uncomfortable and shocked?...They laugh.

Finally, for complete clarity, Sarnoff demands that Levant steers clear of politics, religion and sex.

Oscar: You just took the whole world off the table!...What else is there? Take away the big three, there’s nothing left. What’re we gonna joke about? The weather?...

At length Parr and Levant embark on the interview, and, perhaps inevitably, Levant ignores all the warnings, and cracks jokes about politics, religion and sex.

Oscar: You know what a politician is, don’t you? A man who’ll double cross that bridge when he comes to it.

Oscar: We have a great deal in common, [my wife] and I. Neither of us can stand me… I asked her once if she’d ever divorce me. ”Nah,” she told me. “I’m a good Catholic. I’d murder you instead.”

Oscar: Oh, sex is a topic I can’t resist. I’ve been married for nineteen years, so I’m very nostalgic about it.

After the show, as the recriminations fly, it’s left to Levant’s wife to point out that culpability does not entirely reside with Levant.

June: You don’t book a zebra and then bitch about its stripes. My husband makes people laugh. But laughter’s not innocent, Mr Sarnoff; don’t pretend it is, because that’s a lie. It always comes at a cost. To someone.

Oscar and June Levant

We in the world of commercial communication may recognise the themes explored in ‘Good Night, Oscar’. On the one hand, we don’t want to disturb or upset our audiences. And we are bound to be ‘legal, decent, honest, and truthful.’ On the other hand, we aim to cut through: to earn attention, admiration, affection, recall.

It’s incredibly difficult for Clients and Account Teams to draw the line: to define the parameters of what is acceptable. And while Creatives may not actively seek to cross that line, they will understandably endeavour to dance on it.

Oscar: Analyzing a joke, it’s like dissecting a frog. When you take it apart, you find out what it’s made of, but you kill it in the process.

I’m not sure this is an area where rigid distinctions and literal limitations help that much. Ultimately, what is called for is taste and judgement; an appreciation of where culture is right now; and a commitment to truth.

Oscar: The best jokes? The ones worth tellin’? They’re dangerous on account’a they tell the truth.

'If I expected love when first we kissed,

Blame it on my youth.

If only just for you I did exist,

Blame it on my youth.

I believed in everything,

Like a child of three.

You meant more than anything,

All the world to me.

If you were on my mind all night and day,

Blame it on my youth.

If I forgot to eat and sleep and pray,

Blame it on my youth.

And if I cried a little bit when first I learned the truth,

Don't blame it on my heart,

Blame it on my youth.

Nat King Cole, ‘Blame It On My Youth’ (O Levant / E Heyman)

No. 534