‘Bringing Up Baby’: Recognising the Rules of Attraction

‘Now it isn't that I don't like you, Susan, because, after all, in moments of quiet, I'm strangely drawn toward you, but - well, there haven't been any quiet moments.’

David Huxley, ‘Bringing Up Baby’

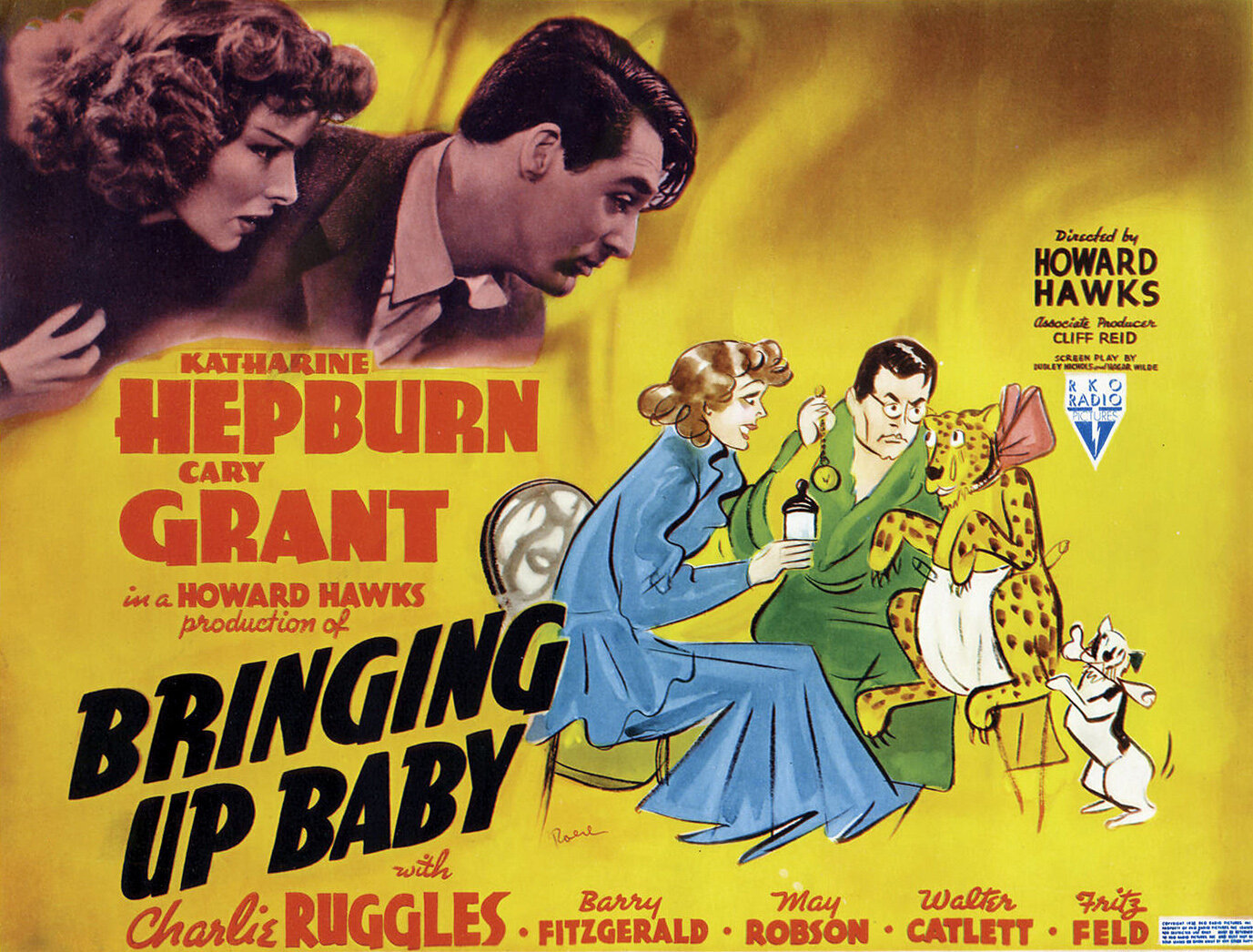

‘Bringing Up Baby’ is a sparkling 1938 romantic comedy directed by Howard Hawks.

The film places charming but eccentric characters in absurd situations, and ensnares them in misunderstandings and misadventures. There’s fast-paced verbal fencing interwoven with farcical physical comedy. There’s an unlikely romance, a whiff of danger and a race against time. There’s a Brontosaurus skeleton missing just one bone, a leading man in a negligee and a leopard that can only be calmed by a refrain from 'I Can't Give You Anything But Love, Baby.' Many consider it the definitive screwball comedy.

A bespectacled Cary Grant plays David Huxley, a mild mannered palaeontologist who is planning to marry his serious minded colleague the next day. While playing a round of golf, he meets free spirited Susan Vance, played by Katharine Hepburn. They quarrel over a missing ball and she dents his car. At a smart restaurant that evening he slips over on an olive she has dropped, lands on his top hat and gets accused of stealing a purse. She has a wardrobe malfunction.

Susan concludes that David is most definitely the man for her.

'I know that I'm gonna marry him. He doesn't know it, but I am.’

After such a challenging set of encounters, David doesn’t seem so sure.

Susan: Well, don't you worry, David, because if there's anything that I can do to help you, just let me know and I'll do it.

David: Well, er … Don't do it until I let you know.

Susan has just been in receipt of a tame leopard named Baby. Giving David the impression that she is in peril, she lures him to her apartment. He pleads with her to make her escape.

David: Susan, you have to get out of this apartment!

Susan: I can't, I have a lease.

Next Susan persuades David to accompany her with Baby to her farm in Connecticut. There follows a series of scenes in which Baby goes missing; Susan’s dog runs off with David’s precious Brontosaurus bone; and another more dangerous leopard escapes from a nearby circus. Ultimately everyone ends up in jail.

Susan: Anyway, David, when they find out who we are, they'll let us out.

David: When they find out who you are, they'll pad the cell.

In the midst of all these madcap adventures Susan encounters a psychologist.

Susan: What would you say about a man who follows a girl around... And then, when she talks to him, he fights with her?

Psychologist: Well, the love impulse in men very frequently reveals itself in terms of conflict…Without my knowing anything about it, my rough guess would be that he has a fixation on you.

This exchange seems to be at the heart of the movie’s characterisation of romance. True love, it suggests, involves internal tension: instinctive attraction encountering rational resistance and emotional uncertainty. It requires conflict to be resolved and struggle to be overcome. To this end Hawks cut several scenes in the middle of the film in which David and Susan declare their love for each other, and he resisted the studio’s request to remove Grant’s glasses.

I read in The Times (6 June 2020) about a study into the nature of human attraction conducted by Professor Gurit Birnbaum from Israel’s Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya.

In previous research Birnbaum has shown that you can increase a potential partner’s interest in you by demonstrating to them that you like them.

'We found that when people feel greater certainty that a prospective romantic partner reciprocates their interest, they will put more effort into seeing that person again, and even rate the possible date as more sexually attractive than they would if they were less certain about the prospective date’s romantic intentions.’

Birnbaum’s more recent study adds a fresh and somewhat contrary perspective. Considering the online conversations of 130 single students, she found that if the object of the students’ affection underplayed their reciprocal interest, then the students were even more likely to desire them; and they would sign off in a way that indicated they would like to meet again.

'Being hard to get signals that potential partners are worth pursuing because they have other mating alternatives and therefore can limit their availability… Potential partners who use this strategy give the impression that they can afford to do so because of their high market value.’

The research concluded that to be successful in the dating game requires a delicate balancing act.

'Daters would be advised to show initial interest in potential partners so as not to alienate them. However, they should keep some cards to themselves. For example, reciprocal and gradual opening up is desirable, spewing one’s emotions without control is not.'

This may all seem rather obvious and to chime with one’s own personal experiences. But how well do we apply the rules of attraction to our own work challenges and to the management of our careers?

Having been employed for many years in a service industry, I found that businesses often do a great deal to signal to Clients that they find them attractive. They fall over themselves in their eagerness to express their availability and enthusiasm for an assignment. But they do very little to suggest that they will be hard to get.

By Birnbaum’s analysis, such behaviour indicates an inferior market value and almost certainly leads to lower levels of commercial success.

As it turned out there was also something a little hard to get about ‘Bringing Up Baby.’ Neither critics nor consumers were initially enamoured of the film, and Katherine Hepburn ended up having to buy herself out of her contract with the disappointed studio. Of course, in time love prevailed: audiences fell for the movie’s sophisticated charms and it became one of the world’s favourite comedies.

David: Now don't lose your head, Susan.

Susan: I've got my head, I've lost my leopard!

'I couldn't bear to be special,

I couldn't bear, couldn't bear.

So don't look at me and say

That I'm the very one

Who makes the cornball things occur,

The shiver of the fur.

Don't expect so much of me.

I'm just an also-ran.

There's a mile between

The way you see me and the way I am.

So, don't stare at me that way.

Of course it gives me pride,

But I won't take on the risk

Of letting down the sweet sweet side.’

Prefab Sprout, ‘Couldn’t Bear to Be Special’ (P Mcaloon)

No. 290